Europe Continues to be the Main Destination for U.S. LNG Supply Exports

Europe likely averted a severe energy crisis this winter with relatively warm weather and filling its storage facilities to more than 90% with strong LNG imports and conservation.

But it could still be facing a crunch in the winter of 2023-24 because of reduced access to Russian gas and a potential reluctance by China to redirect its U.S. LNG volumes to Europe.

The global LNG market was upended in 2022 as Europe paid record prices to attract flexible supplies from the U.S. and other regions in an effort to replace pipeline supply from Russia.

With continued unusually warm weather so far this year, FOB U.S. Gulf Coast LNG cargo values assessed by OPIS have moved down significantly from the record average $100.27/MMBtu that was seen for the four 15-day loading windows set on Aug. 26, 2022, just days before Russia halted gas deliveries to Germany via the Nord Stream pipeline. So far in 2023, FOB values have averaged $17.823/MMBtu, less than half of the average value of $36.435/MMBtu in the fourth quarter last year, but cold weather or even normal weather next winter could lead to shortages and high prices.

“Unlike with oil, where at least some of it, or even a significant part, can be redirected to other places and free non-Russian oil to go to Europe, this is not the case of Russian gas,” Anna Mikulska, a fellow at the Center for Energy Studies at Houston’s Rice University, said in an interview. “Thus, Europe ends up competing on the global LNG market for additional volumes to replace as much of Russian supply as possible, effectively tightening the market in a significant way and competing with other markets, particularly in Asia. The effect we have already seen is sky high prices of gas.”

U.S. LNG has been the primary source of supply to help offset the loss of more than 1.766 Tcf of Russian gas shipments to Europe in 2022, Anatol Feygin, chief commercial officer at the largest U.S. LNG exporter, Houston-based Cheniere Energy, said.

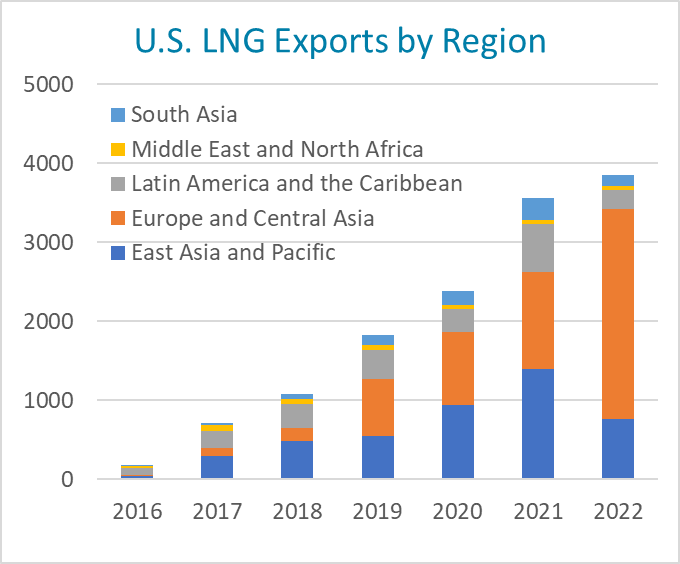

Europe has historically been the market of last resort for U.S. LNG because it has typically paid lower prices than Asian buyers, but in 2022 Europe and Central Asia accounted for 68.9% of U.S. LNG exports, or a gas equivalent of 2.655 Tcf, according to an OPIS analysis of the latest data from the Department of Energy.

Europe has historically been the market of last resort for U.S. LNG because it has typically paid lower prices than Asian buyers, but in 2022 Europe and Central Asia accounted for 68.9% of U.S. LNG exports, or a gas equivalent of 2.655 Tcf, according to an OPIS analysis of the latest data from the Department of Energy.

In 2021, Europe and Central Asia imported 1.218 Tcf of U.S. LNG, or 34.2% of the total U.S. exports.

East Asia and the Pacific in 2022 received 19.7% of U.S. exports, or 760.9 Tcf, about half of its 2021 proportion of 39.3% (1,400 Tcf). Asian buyers with long-term U.S. LNG contracts diverted many of their cargoes to Europe in 2022 to take advantage of high prices on the continent. But China may be less likely to do that this year given that its demand is expected to increase after it abandoned its strict Covid-19 lockdown policy.

Europe was the most attractive indicative market for U.S. Gulf Coast LNG almost every day in 2022, with OPIS-calculated notional netbacks based on the Netherlands’ TTF or the U.K.’s National Balancing Point (NBP) virtual gas hubs having an average advantage of $3.206/MMBtu through Dec. 21 over notional netbacks based on the Japan Korea Marker (JKM) LNG spot price for northeast Asia.

In 2021, notional netbacks based on the JKM had an average advantage of $1.437/MMBtu over Europe’s notional netbacks.

Europe will likely continue to be the most attractive indicative market for U.S. supplies this year, as the 2023 calendar strips show the European TTF benchmark gas prices with advantage over spot LNG futures prices for northeast Asia.

Although the European Union imposed strong economic sanctions over Russia’s Feb. 24, 2022, invasion of Ukraine, the bloc never sanctioned Russian gas imports because the continent was so reliant on the fuel.

Before the invasion, Russia accounted for as much as 40% of Europe’s gas supply, with 2021 deliveries totaling 5.474 Tcf, according to Reuters. The Nord Stream pipeline from Russia to Germany was the largest conduit for Russian gas, typically carrying about 5.9 billion Bcf/d before the invasion of Ukraine.

Russia cut Nord Stream deliveries to 40% of capacity after it invaded Ukraine and in late July it reduced flows to 20% before halting deliveries altogether in early September.

On Sept. 26, the Nord Stream and parallel Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which had not started commercial operations, were sabotaged with explosives in the Baltic Sea. The assailants have not been identified.

In the late summer and early fall, Europe drove TTF and FOB U.S. Gulf Coast LNG prices to record levels as it scrambled to fill storage during the typically lower-priced shoulder season. After those storage facilities were filled to more than 90%, FOB U.S. Gulf Coast LNG fell and averaged $35.896/MMBtu from mid-October to mid-December.

To try to avoid huge price spikes in 2023, the EU energy ministers in early February 2023 agreed to cap the price that member states would pay for natural gas, The Wall Street Journal reported.

The likelihood that the cap would be needed has significantly been reduced with the warm winter in Europe, lower gas consumption and increased coal and nuclear output.

European Union gas storage facilities reached a fullness level of 96% in November and last week fell to about 64%, significantly higher than the five-year average of about 45% for this time of year, according to Reuters. By the end of the current heating season on March 31, the fullness level is expected to drop to 55%. Even if the 100-billion-cubic-meter (3.531-trillion-cubic-feet) storage facilities are full, they would only meet about one-quarter of Europe’s gas demand, the report said.

The cap could have taken effect as early as Feb. 15 if month-ahead TTF prices remain above 180 euros/MWh ($56/MMBtu) on the Intercontinental Exchange for three consecutive days and are at least 35 euros higher than a reference level for global LNG prices over the same period.

For reference, from Aug. 1 through Sept. 15, 2022, prompt-month TTF prices averaged $68.22/MMBtu.

The cap would apply for 20 business days to month-ahead, three months-ahead and year-ahead derivative contracts, but would not apply to over-the-counter trades, day-ahead or intraday trading. Germany opposed the cap out of concerns it would make Europe less competitive for flexible LNG supplies compared with Asia.

ICE warned it could move its gas market outside the EU if the cap is imposed because it was worried traders might be required to provide tens of billions of dollars in additional cash for margin payments. The move could push some traders to buy and sell gas and LNG under bilateral deals rather than use benchmark indexes.

EU officials said the cap could be suspended if it would risk gas supply security to its member countries financial stability or the flow of gas in Europe.

To prepare for next winter, the EU will require gas storage facilities to be at least 90% full Nov. 1, up from 80% in previous years, and Germany will mandate an even higher level of 95% by then, Mikulska said.

Although the price cap and storage mandates are designed to help consumers, they would likely have “unintended negative consequences” if implemented, she said.

Despite the higher-than-normal storage levels so far this winter, Europe would likely pay historically high prices for LNG this year and could still face an energy crunch in the winter of 2023-24 because much of the Russian volumes that were still flowing at times in 2022 will not flow this year, analysts have said.

Europe imported 62 billion cubic meters of Russian gas in 2022, which was 60% less than the average in the previous five years, Reuters said, citing European Commission data. This year, Europe’s imports of Russian gas are expected to drop to 25 billion cubic meters, according to the International Energy Agency.

If the price cap is implemented, it would “just provide information to other points of demand how much they need to bid to outbid Europe, which will cause redirection of gas to other places,” she said. “In general, that would lower prices of LNG on global markets but would also mean that Europe would not be able to attract cargoes. So, the only way to keep cargoes coming to Europe would be keeping it competitive — price cap would then mean that the governments will cover the difference — a very expensive endeavor that will at the end have to be paid by consumers via taxes.”

The International Energy Agency in December said that despite EU measures to promote energy efficiency and a recovery this year off decade-low levels in nuclear and hydropower production, the continent still could face a gas supply gap of 953 Bcf in 2023 if deliveries from Russia drop to zero and China’s LNG imports rebound to 2021 levels.

Europe has vowed to end its dependence on Russian natural gas. It is building additional LNG import capacity to allow it to increase imports, with terminals in The Netherlands and Finland completed in the second half of 2023 and three German terminals scheduled to come online in 2023 as well.

Europe is expected to add about 7.9 Bcf/d of LNG import capacity in 2023 and at least 1.3 Bcf/d more in 2024, Cheniere’s Feygin said.

But because it takes about four to five years to build an LNG export plant after it is financed, global LNG market will likely “remain tight for the next several years,” he said.

Nearly all of the LNG capacity of about 17.3 Bcf/d under construction around the world “is required to backfill Russian piped gas to Europe in the long run,” so now many projects will need to be financed to supply growing demand throughout the world, U.S. LNG developer Tellurian.

Despite Europe’s need for more LNG, European customers for the most part are still not supporting additional U.S. LNG projects with 15- to 20-year deals under which they would pay Henry Hub rates for gas supplies and a take-or-pay liquefaction fee in an estimated range of $2-$3/MMBtu.

European countries in recent years have shied away from procuring U.S. LNG under long-term deals not only because Russian pipeline gas was abundant and cheaper, but also because they are concerned that supporting hydraulic fracturing practices in the U.S. would conflict with their goals to reduce carbon emissions.

The U.S. became the world’s largest LNG exporter in the first half of 2022 as the six existing plants operated at about capacity and a seventh plant — Calcasieu Pass LNG in Louisiana — came online and steadily ramped up output.

U.S. LNG exports averaged 11.5 Bcf/d in the first quarter of 2022, accounting for about 23% of global trade of 49 Bcf/d but fell to an average of 10.8 Bcf/d in the second quarter as the Freeport LNG plant in Texas was shut on June 8 by a fire at the facility, according to the Energy Information Administration. It was the first time that a U.S. LNG export terminal was closed for an extended period because of an accident.

U.S. exports are expected to reach a new record in March 2023 of close to 12.5 Bcf/d and climb to 12.7 Bcf/d by the end of 2023, EIA added. No new facilities are scheduled to come online in 2023, but the 15 million mt/year Golden Pass in east Texas is scheduled to start operating in 2024.

A few proposed U.S. LNG projects are eyeing final investment decisions this year, with San Diego-based Sempra’s 10.5 billion, 13.5 million mt/year first phase of the Port Arthur LNG project in east Texas one of the most likely after signing long-term deals for most of that capacity.

–Reporting by Ron Nissimov, rnissimov@opisnet.com; Editing by Jeff Barber, jbarber@opisnet.com, and Barbara Chuck, bchuck@opisnet.com

To stay on top of this market, make sure you’re receiving

OPIS North America LPG Report. Try this daily report for free.