Popping the Bubble of Fuel Freight Rates

Crude oil and refined product futures prices have been sliced in half since the oil price renaissance of 2011-14, but the tumble in those widely traded contracts pales in contrast to the outright collapse in the cost of moving physical petroleum by boat along U.S. coasts.

Not long ago, fuel freight rates from the Gulf Coast to the Lower Atlantic were four, five or even six times what they are these days and maritime sources believe that the U.S.-flagged oil tanker rate environment might get worse before it stabilizes.

Plenty of analysis has been devoted to crude oil cost “bubbles” that have expanded and popped in the last 11 years, but the implosion of the freight bubble occurred in slow motion.

The height of high shipping costs came with the first rise of U.S. shale production. But a lot has changed since those 2011-15 production surges caught crude transporters short on logistics and freight rates are not rising with the current boom.

Flash Back to 2014

A three-year comparison starkly contrasts the fuel freight rates for Jones Act vessels from the U.S. Gulf Coast to the East Coast.

For example, in 2014:

- ExxonMobil booked the vessel American Phoenix on a 12.5-day round trip to Florida at approximately $120,000 per day.

- That “top-of-the-market” deal resulted in a simple freight cost of about $1.5 million on 350,000 bbl of gasoline, or approximately 10.2cts/gal.

Thanks to dock costs and other charges it was not uncommon in 2013-14 for Gulf Coast gasoline to cost 10-15cts/gal to move to Miami or Jacksonville, Fla.; Savannah, Ga.; or Charleston, S.C. – if, indeed, vessels could be located. Marketers along the coast were often told that suppliers wouldn’t commit for fuel supply at these waterborne destinations even at rates close to 15cts/gal.

Suppliers weren’t the singular segment convinced of lasting high fuel freight rates. A Norwegian investment bank rendered a spring 2014 forecast that suggested that Jones Act tanker rates might average close to $85,000 per day clear through to 2020.

Ships to move gasoline and diesel were scarce, thanks to higher Gulf Coast production, but also because many vessels were converted to carry crude oil between Gulf Coast ports. Moving light tight oil from Corpus Christi, Texas, to St. James, La., for example, soaked up a number of tankers and barges and took precedence over fuels’ movement.

No One Anticipated How Quickly the Fuel Freight Market Would Change

A key early contributor to the decline came when U.S. Lower 48 oil production crashed by more than 1 million b/d from a peak 9.626 million b/d in April 2015 to just 8.545 million b/d 18 months later. Barges and tankers that were switched from clean freight to dirty freight were switched back to the clean products’ transport. Meanwhile, the lifting of the longtime crude oil export ban allowed for U.S. crude to move overseas via cheap foreign tankers.

The lifting of U.S. crude ban helped to narrow the Brent-WTI crude price spread, which allows U.S. refineries to jack up foreign crude imports. This led to a lower demand for U.S. crude deliveries via ships.

The period also saw a huge buildout of pipelines and other logistics so that oil could freely move between Houston and Louisiana via pipeline. That also enabled more vessels to return to the clean products market.

And finally, the export market for U.S. manufactured refined products quickened, while Renewable Identification Number avoidance hastened the movement of gasoline and diesel to offshore destinations via foreign flagged vessels, cutting demand for Jones Act barges and tankers.

2017: Forget Double Digits; Ships Now Moving Fuel for “Just a Few Cents”

Suppliers are now more than willing to bid on term deals for gasoline or diesel into the same Lower Atlantic ports that they spurned three or four years ago. In fact, it’s generally recognized that several major Gulf Coast refiners are not just long on gasoline – they are also long on dock space and domestic freight.

One affiliate of a convenience-store chain recently brought gasoline to Tampa, Fla., at a cost of just 5cts/gal over Gulf Coast pipeline mean. Normally, spot gasoline commands a premium of about 1-1.5cts/gal for availability at a waterborne dock, so the voyage underscores just how competitive waterborne destinations have become.

Shipping sources said some U.S.-flagged ship owners are operating in negative margins due to spot ship hires commanding rates below ship operating costs. The weak shipping environment could be a catalyst for early scrapping of older ships.

Some current numbers:

- Shipping sources tell OPIS that the “all in” cost to move a cargo of gasoline from Gulf Coast refineries to Lower Atlantic ports is now only about 3.25cts/gal, or just $20,000-$22,000 per day.

- That is down sharply from average spring spot charter rates of about $45,000 per day, which reflect a fall from about $60,000 per day in the first quarter of 2017.

- Some suppliers believe per-diem rates could slip below $20,000 before a bottom is reached.

And there are more vessels to come. A Kinder Morgan subsidiary took delivery of a second Jones Act tanker earlier this year named the American Freedom and it is due to get two more vessels as part of the overall deal. More boats are coming. Sources believe that another 40,000-ton Jones Act vessel will be commissioned in September with yet another similar-sized vessel in October.

“There is too much freight,” a marketer told OPIS. “Rates are going to be cheap, cheap, cheap.”

Mega-retailer Wawa will get its own articulated tug barge (ATB) from Fincantieri Bay Ship Building before year’s end as well. The oceangoing tank barge has a storage capacity of 185,000 bbl. Wawa ordered the ship because it has very aggressive expansion plans in the Sunshine State and was apparently worried about stable fuel freight rates. Meanwhile, competitor RaceTrac has a two-year time charter at an estimated cost of $40,000 per day for the Independence. Shipping sources believe the charter expires in 2018.

Ramifications for the Market

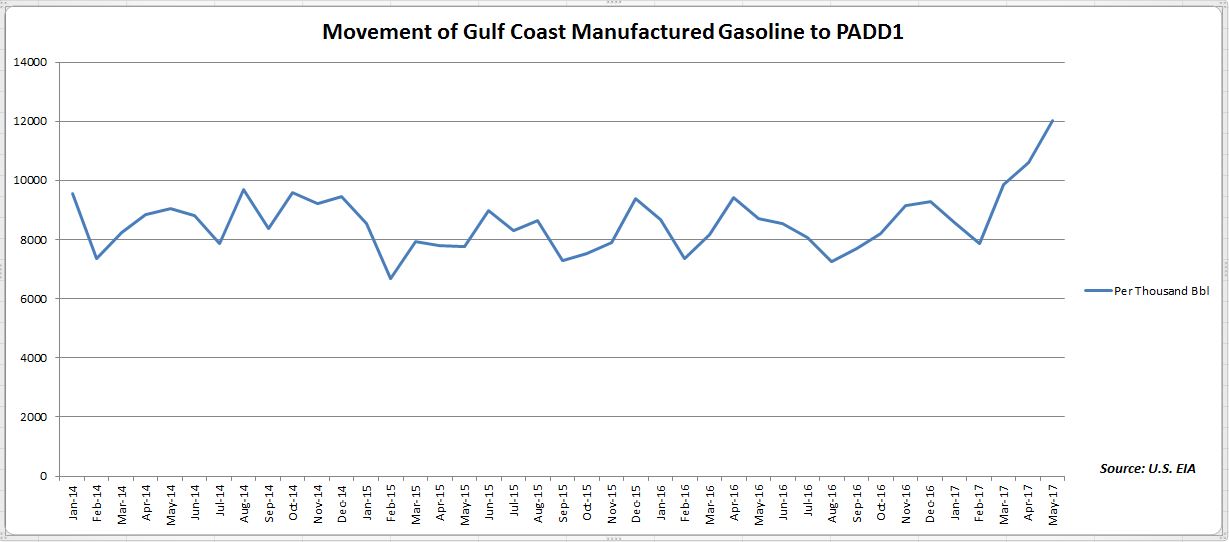

EIA data confirms that there has been explosive growth in the movement of Gulf Coast manufactured gasoline to PADD 1. Recent monthly data showed 12 million b/d of gasoline blending components (various BOBs) traveling from PADD 3 to PADD 1 by tanker and barge. That compares to 8.7 million bbl in May 2016 and just 7.7 million bbl in May 2015.

But Jones Act rates can be fickle and volatile and demand for the boats could swell or swoon based on changing product flows.

To conclude, we’ll leave you with 4 points to consider:

- If long-term import trends continue, it’s conceivable that some U.S.-flagged vessels might make longer trips from the U.S. Gulf Coast to ports from Baltimore north. A recent EIA report surprised traders with nearly 1.1 million b/d of imports, but the trend has clearly been toward less – not more – European gasoline arriving in the U.S.

- With cheap waterborne fuel freight rates, it’s difficult to conceive of line space premiums returning for Colonial Pipeline any time soon. The high cost of waterborne movement and fully allocated Colonial cycles led some shippers to pay as much as 20cts/gal for space on Line 1, but that largely occurred in the 2014-15 period. There is the suspicion that next year will see some suppliers remove clauses designed to treat line space surcharges, since those clauses have resulted in discounted product.

- Pipeline terminals such as North Augusta, S.C., or Bainbridge, Ga., meanwhile, may never see the brisk loadings that occurred when waterborne rates were sky-high.

- And finally, one has to wonder about projects like the Florida Fuel Connection that were designed to bring fuel from Louisiana refineries via rail to the peninsula. Other efforts at railing product to the state have fallen by the wayside, although much of the state’s support for Florida Fuel Connection is attributable to the desire to cut back on transport truck traffic in the state.

OPIS Executive Editor Edgar Ang contributed to this blog.