High Costs, Geopolitical Risks Impede Blue Carbon Removal Projects

Demand for voluntary blue carbon credits from companies seeking to fulfill net zero pledges has surged in recent years, but geopolitical risks, limited verification capacity and high startup costs will likely prevent blue carbon credit supply from scaling up for years to come.

Companies want blue carbon credits — which are generated by coastal carbon sequestration projects — for their high quality and ability to diversify carbon storage portfolios.

But blue carbon projects account for just a handful of the 2,158 projects registered by Verra, a leading carbon credits registrar and verifier.

From April 21, 2022: ‘Huge Momentum’ is Underway for Blue Carbon

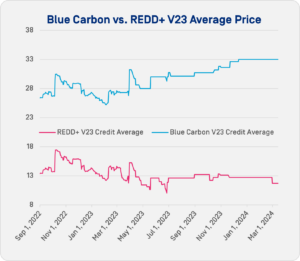

High demand for the credits and relatively expensive project costs have pushed the offsets to a substantial premium over forest-based credit alternatives in the voluntary carbon market.

OPIS calculated the Blue Carbon V23 Credits Average at $33.01/mt on March 13. On the same day, the REDD+ V23 Credits Average was calculated at $11.71/mt.

“It’s what everyone wants, but no one can get,” Arthur Wace, sustainability consultant with London-based carbon risk management and procurement firm Redshaw Advisors, said. “We have clients that have made net zero commitments for 2030 or even 2025. They want to invest in projects now. But the risks are too high.”

“It’s what everyone wants, but no one can get,” Arthur Wace, sustainability consultant with London-based carbon risk management and procurement firm Redshaw Advisors, said. “We have clients that have made net zero commitments for 2030 or even 2025. They want to invest in projects now. But the risks are too high.”

Sources said there are a few reasons for that, including that the blue carbon verification and credit issuance system is still in its early stages.

Project methodologies continue to develop, and it remains difficult and costly in many parts of the world to accurately measure the carbon stored in blue environments.

Further, it requires significant startup capital to begin to restore a coastal environment and it takes years to realize profits from credit sales. And many countries with blue carbon projects have yet to decide how to govern them. “The market is not in a position to scale,” Wace said. “But we’re getting there.”

Carbon Accumulation Rates Vary

As methodologies develop and researchers learn more about blue carbon environments, their climate diversity and carbon storage capacities are becoming clearer. Coastal mangrove forests, salt marshes and seagrass beds typically store carbon at a higher rate than forests and for longer periods.

Scientists estimate wetland environments store carbon at 10 to 20 times the rate of land forests, but others caution that comparisons are tough to make because of wide variations in both ecosystems. And while coastal wetland environments around the world are under threat globally, there’s no risk of them burning during periods of drought.

From April 20, 2022: Blue Carbon Pioneer Says Mangrove Tree Is the ‘Best Climate Machine’

A research team led by University of North Carolina Professor Antonio Rodriguez studied carbon deposits in salt marshes along North Carolina’s coast. In a study published in July in Nature, the group detailed the variations that occur depending on the age and growth of the ecosystem.

“If you look at carbon burial at different time scales, you get vastly different values,” Rodriguez said.

When salt marshes degrade, they begin to release the carbon they have stored.

But when restoration begins, as Rodriguez and his team found, carbon accumulation rates are high. Rates plateau as the ecosystem matures, but most of the carbon sucked from the atmosphere remains.

“That’s really important for offsetting because if you restore a salt marsh, then you’re going to benefit from that increased burial right away,” he said.

What’s more, as sea levels continue to rise, researchers expect the area viable for salt marshes will expand.

‘Can we even do this?’

Liz Guinessey is Verra’s food and blue carbon innovation manager and wetlands expert. Before that, she investigated GHG emissions and carbon storage in Georgia’s coastal wetlands for her master’s thesis.

“Back then, it was this question of, ‘Can we even do this? Can we get the quantification down pat enough to be able to potentially bring this carbon that gets stored to market?'” Guinessey said.

Despite the challenges, she said Verra has managed to develop ways to do so with confidence. “I think we’ve been able to figure out ways to deal with that uncertainty, deal with those fluctuations, and still be able to very clearly estimate at a conservative level what’s actually stored,” Guinessey said.

Still, blue carbon credit verification remains a developing practice. Verra released its first blue carbon methodology in 2020 and has since added three more. The organization is now in the process of consolidating the three into a single document.

Competing registry Gold Standard has not finalized blue carbon methodologies, although it said it’s developing a mangroves methodology with FORLIANCE.

Sources also said it can be challenging to find researchers with the expertise needed to verify a blue carbon project’s impact. And it’s a dirty job.

“Most are muddy, mucky environments,” Guinessey said. “You get literally absorbed by mud a lot of the time. These are not great conditions for field work. But I think that we’re getting to a point where it’s not becoming as challenging, especially with new technologies like remote sensing.”

Geopolitical Risk

As blue carbon methodologies develop and experts learn to understand and measure the environmental conditions, governments have grown wary of voluntary projects.

In one case, the blue carbon project known as Tahiry Honko was launched in 2014 by UK-based Blue Ventures and 10 small communities in Madagascar.

But in 2018, the Malagasy government argued the communities had signed a bad deal and placed a moratorium on the sale of carbon credits. None from the project have been sold, according to Mongabay, an online conservation news outlet. A number of voluntary offset projects that predate the moratorium remain in limbo.

Actions by other governments could also affect the projects.

India’s Power Minister Raj Kumar Singh in August announced a ban on the exports of carbon credits, though the government has offered no further information.

Some sources believe Singh was referring to carbon credits that would apply to India’s new compliance market, rather than those that would be sold on the voluntary market.

In recent months, Papua New Guinea, Honduras and Indonesia also have announced moratoriums on the sale of some credits. And many other countries have stepped in to regulate the voluntary market in some way.

“So many of these coastal systems are considered public goods under different jurisdictions,” Guinessey said. “So, getting either the government to sign on to a carbon project or figuring out some sort of concession to allow for a group to move in and actually develop a project can be a barrier.”

Where Are Blue Carbon Credits Headed?

Along with geopolitical risks and limited global blue carbon credit capacity, project finance is also a problem. Restoring blue environments is costly and it can often take several years before developers are able to start selling credits.

A number of companies are working to reduce the risks of carbon offset projects in general. Verra is developing credits that can be sold to generate startup capital to projects just getting off the ground. Insurance providers have also begun to underwrite projects against the potential invalidation of credits issued.

Still, the barriers to entry, particularly for communities in developing countries, remain high, sources said.

Analysts, however, expect buying interest in blue carbon credits will continue to rise.

“There is a general undersupply, and these projects are perceived to be of very high quality,” Anop Pandey, manager of market analysis for ClearBlue Markets, said. “We believe that any new supply will certainly get bought up quickly.

Also, as offset usage by corporations continues to receive more scrutiny, there will be more pressure for corporations to show the offsets they are using are of a high quality with large emission reduction and removal benefits.”

Stronger demand for the credits and price premiums are helping development efforts.

“In 2019-2020, you could buy a carbon credit from a REDD+ project for $6, $7,” Wace said. “Now, as prices have come up, we can begin to bring on higher impact projects.”

At the same time, the buyers for blue carbon offsets are mostly large tech companies with significant cash flows.

“Will other corporate industries be willing to pay for these projects?” Pandey asked. “In other sectors with companies that have smaller budgets for offset purchases, but still have high emissions, maybe not. As such, the demand and supply of these projects will need to find a balance.”

Blue carbon projects face other risks, including the environments’ ability to survive and continue to sequester carbon for decades.

During six-month period in 2016 and 2017, for example, between 40 and 50 million mangrove trees in Australia’s Gulf of Carpentaria died. The culprit was an exceptionally harsh El Nino climate that dropped coastal water levels by 40 centimeters for roughly six months.

Still, with cooperation between government and private industry, experts expect blue carbon credits will eventually provide a crucial, high-quality means of carbon sequestration at scale. But it remains impossible to say exactly when that will come to pass.