Nature-based Carbon Removal Credits: Slow Growth Expected Despite Record Demand

Nature-based carbon removals projects can create valuable credits that command price premiums over avoidance and reduction credits. But they are also hard to scale, and it will take years to meaningfully increase stocks of forestry removals credits in the voluntary carbon market.

Several headwinds have slowed nature-based carbon removal credit issuances. They include difficulty in getting some auditors to regularly verify stored carbon, a short supply of appropriate land and difficulty in persuading property owners to transition from agriculture production or other uses.

In the face of criticisms regarding project integrity, developers want to proceed slowly to ensure their projects produce reliable, high-quality credits. Meanwhile, popular Blue Carbon and Afforestation, Reforestation and Revegetation projects face a more fundamental speed limit: it takes time and resources to grow a tree.

From Degraded Field to Forest

Nature-based carbon removal projects involve replanting degraded or cleared ecosystems. The trees and vegetation they grow actively remove carbon from the atmosphere.

By comparison, reduction projects reverse deforestation, install carbon-free power generation or replace cookstoves with more efficient devices that emit less greenhouse gases, among other activities. Land conservation projects avoid emissions that would have otherwise occurred.

Many ARR developers have highlighted how difficult it can be to grow a forest on cleared land.

U.S.-based developer GreenTrees partners with landholders in the Mississippi Alluvial Valley to convert their properties into ARR projects. In most cases, owners previously used their land to farm crops like soybeans and corn.

According to GreenTrees Co-Founder and Managing Partner Chandler Van Voorhis, that land-use transition can be a tough sell.

“With [Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation] and [Improved Forest Management] projects, you’re changing the way you manage an existing asset,” Van Voorhis said. “With ARR, you’re making big capital investments. You have different yield curves. You’re going from a known cash position to uncertainty. That is a different kettle of fish.”

Van Voorhis described carbon removal and resulting profits from an ARR project as an S curve.

It can take several years before a new project begins to generate credits and, in those early years, issuances are typically meager.

Landowners should look at afforestation not as they would a crop, but as a generational change in how they use their land, Van Voorhis said.

One ARR project getting underway in the Democratic Republic of Congo exemplifies the slow pace at which afforestation occurs.

Project developers ALLCOT A.G., Graine de Vie and Fanyatu have allotted 9,400 hectares to regrow with a mix of forest and fruit trees that will provide a cash crop for participating communities to sell. In their project description filed with carbon credit issuer Verra, the developers expected to remove zero greenhouse gas emissions in the first year. The second year is projected to remove just under 4,000 metric tons. But by the 10-year mark, the project will possibly remove more than 600,000 mt of C02 per year.

Keeping Growth Slow to Maintain Quality

REDD+ projects have received criticism over the last year for alleged errors in emissions avoidance calculations.

ARR developers are worried about the potential for similar criticisms and want to take steps to ensure their projects reliably sequester carbon. But doing so can further slow the pace of growth, sources said.

U.S.-based Chestnut Carbon launched in 2022 and started to regrow land they own and manage. The company announced their first contract with Microsoft in December 2023 for the forward delivery of 362,000 ARR credits. But the first credits won’t be delivered until 2027.

The deal comprised roughly 70% of the credits the company expects to issue from their first project, Chief Commercial Officer Shannon Smith said. “Part of that is just giving us a delivery cushion to make sure that, if there’s any shortfall in credits the trees actually deliver, we won’t have any trouble meeting our obligations,” Smith said. “But we’re also leaving some credits to sell on the spot market because we’re expecting the credit prices to be higher five years from now.”

According to Chestnut Carbon Chief Financial Officer Greg Adams, it would theoretically be possible to plant forests that grow faster and issue credits sooner. But that could sacrifice the project’s quality.

“We do not want to overpromise and under deliver,” Adams said. “We want to make sure we do it right. Given the criticism that has been leveled against this space, it’s really important to us that our growth does not come at the expense of compromising the integrity of our product. Full stop.”

Due to the slow pace and significant upfront costs, ARR project proponents have developed creative and diversified business models that do not favor rapid expansion. Many are also combined with community development or biodiversity initiatives.

The Australian organization WithOneSeed launched an ARR project in Timor Leste in 2010.

The country experienced significant deforestation in the 20th century, in part, due to its invasion and occupation by Indonesia from 1975 to 1999.

WithOneSeed supplies farmers with tree seedlings and pays them 50cts per tree per year through ARR credit sales. As of 2023, farmers participating in the project were managing more than 450,000 trees.

Forest First Colombia was also established in 2010 in the Vichada region of the Latin American country where much of the landscape has become degraded grasslands. The company generates revenue by growing a portion of trees to be harvested for timber, while the rest are set aside to develop into a forest and produce removal credits. Registered under Verra’s Climate, Community and Biodiversity Standards, it provides employment to 200 people in the area and has established a wildlife habitat for several threatened species.

“If you have unlimited funds, you could replant an area and just leave it, right?” said Forest First Co-Founder and Chief Financial Officer Jonathan Dodd. “That’s a very benevolent way to do it. But doing that on any scale is really impractical. You have to marry financial return with the ability to provide this sequestration with the co-benefits.”

ARR, Blue Carbon Prices Up with Demand

Demand for removal credits has remained strong, in part, because many buyers believe they have a higher climate impact than other types of credit. These projects not only reduce emissions in the atmosphere but potentially create numerous other benefits for their surrounding regions, including increased biodiversity, erosion reduction and boosted soil nutrients.

As media and academic criticisms of REDD+ projects have intensified over the past year, many buyers have sought out removal credits as a higher-quality alternative.

Removal credit retirements for projects registered with Verra, Gold Standard, Climate Action Reserve and the American Carbon Registry hit a record high of 19 million in 2023, up from 18.3 million in 2022, according to ClearBlue Markets Manager of Market Analysis Anop Pandey.

But while demand for removal credits is on the rise, supply remains low. The total stock of credits in the global voluntary carbon market is dominated by reductions and avoidances, and that share is growing.

Removal issuances fell steeply last year. Total issuances for carbon offset projects under the same registries came in at 249.68 million credits in 2023, Pandey said. Of that, just 11.5 million were from nature-based removal projects.

By comparison, removal projects issued 25.1 million credits in 2021 and 24.3 million credits in 2022.

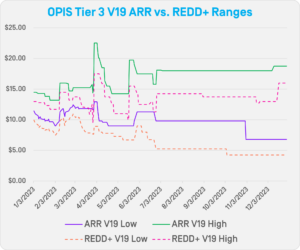

Strong demand and low supply caused ARR prices to maintain a steady premium over REDD+ through the year.

Looking at V19 – a vintage that maintains a significant source of supply in the market – the average OPIS ARR assessment began 2023 at $12.553/mt. It hit a yearly low of $10.683/mt in February, jumped to a yearly high of $17.303/mt in March and finished the year at $12.158/mt.

By comparison, the REDD+ V19 average assessment started 2023 at $11.053/mt, just $1.50 below ARR. It hit a high of $12.85/mt in March, sank as low as $7.483/mt in June and finished the year at $9.125/mt.

By comparison, the REDD+ V19 average assessment started 2023 at $11.053/mt, just $1.50 below ARR. It hit a high of $12.85/mt in March, sank as low as $7.483/mt in June and finished the year at $9.125/mt.

The average prices mask wide fluctuations related to perceived credit quality. The spreads between the low and high of the OPIS assessments for ARR and REDD+ widened significantly over the course of the year.

ARR V19 Tier 3, which reflects a volume of 2,000 to 49,000 credits, started the year in a range of $11.46/mt to $14.48/mt. By Dec. 29, the range had widened to $6.80/mt to $18.75/mt. REDD+ V19 Tier started the year in a range of $9.96/mt to $12.98/mt and that range had widened to $4.25/mt to $16/mt in December.

Some developers said they have signed forward deals far above the OPIS range. The Brazilian ARR developer Mombak publicly reported a deal with McLaren Racing in November for the sale of credits at over $50/mt. OPIS has been unable to verify key details of the transaction, such as the overall volume of credits delivered.

One source has reported selling ARR credits at an even higher rate, but that could not be confirmed by OPIS.

The Outlook for Removal Credit Supply

Due to the slow growth of credit issuances and a general lack of available land to develop more removal projects, analysts do not expect there will be a strong rise in removal issuances in 2024.

“The long time needed to be able to start monetizing credits, combined with the high costs needed to develop these projects, would limit the number of nature-based removal credits that could be produced, despite the expected increase in demand,” Pandey said. “It’s also becoming increasingly difficult to get lands for ARR. Convincing the investors that the project is not going to engage in conversion of native ecosystems is getting harder, as many VCM [stakeholders] increasingly frown upon this as ever-restrictive environmental and social safeguards are put in place.”

Maintaining the pace of issuances has also become a challenge for some developers. Van Voorhis of GreenTrees says his aggregated project ideally issues every year to both satisfy forward sales agreements and return revenue to participating landowners on a regular basis.

But the monitoring, reporting and verification process has slowed, in part, due to difficulties related to getting GreenTrees’ project verified by certified third parties. “First, you need to get on a verifier’s schedule,” Van Voorhis said. “Then you can start verification, which can take nine months. It’s an intensive audit. If you start in January, and you’re lucky, you get credits by September. That’s in an ideal world. The reality is there are so many projects and only so many verifiers. We can’t even get an initial meeting with verifiers until later this year. Sometimes the issuance schedule has nothing to do with us.”

Dodd of Forest First Colombia also initially sought an annual verification process to keep up with forward delivery agreements. But he says COVD-19 slowed project growth in unexpected ways. “The pandemic inhibited our ability to plant and inhibited our ability to raise money,” Dodd said. “In fact, it still does to a degree. So as of today, we’re behind where we thought we were going to be in 2018.”

Ultimately, the project developers OPIS contract by OPIS expect increased demand will be bullish for removal prices. But at least in the medium-term, there’s little hope that issuances will meaningfully increase supply.