True Costs of EU’s Russian Diesel Ban Emerge One Year Later

Twelve months ago, on Feb. 5, 2023, the European Union effectively relinquished its main source of diesel supply by implementing a ban on imports of oil products from Russia. The continent has so far been able to find new sellers, but the current situation in the Red Sea is a reminder of how vulnerable European supply security has become.

For many decades, Europe has relied on Russia for its energy needs. Moscow’s cheap natural gas and crude oil were too convenient to ignore. So when Russia expanded its refinery capacity during the 2010s, Europe took advantage quickly. Imports of Russian diesel jumped to almost 25 million metric tons in 2017 from 6 million mt in 2012. This meant lower fuel prices for European drivers, lower costs for the industry – and more cash pouring into Russia, funding Vladimir Putin’s regime.

The deal was so good that Russian supplies increased to account for nearly half of the EU’s annual diesel imports. However, in February 2022, everything changed. Putin decided to invade Ukraine, and the G7 countries retaliated with sanctions on Russia’s main source of income – the oil and gas industry.

The EU announced a ban on imports of Russian crude and oil products from December 2022 and February 2023, respectively. This meant that Europe was obliged to find new sources for some 25 million mt of annual diesel imports, and Russia would also need to redirect the same volumes elsewhere.

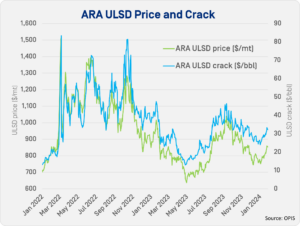

With traders scrambling to make sense of the sanctions, markets rushed to reflect the new, worrying reality. The European ultra-low-sulfur diesel (ULSD) crack, which had averaged just under $8/barrel in 2021, jumped to $40/bbl over the first month after Russia invaded Ukraine and soared to $63/bbl after the oil ban was announced.

One year later, ULSD crack values have eased to around $30/bbl, still high compared with historical levels. The market has managed to keep diesel flowing to where it’s needed, but this has come at a cost, particularly for the European economy.

One year later, ULSD crack values have eased to around $30/bbl, still high compared with historical levels. The market has managed to keep diesel flowing to where it’s needed, but this has come at a cost, particularly for the European economy.

On one hand, Russia has defied expectations, maintaining diesel export volumes broadly unchanged throughout 2023 by finding new buyers across the developing world. Some refiners, particularly in Turkey and the Middle East, have taken the opportunity to buy discounted Russian diesel for domestic consumption, redirecting their own production to Europe instead. Other countries like India have stepped in to take discounted Russian crude to maximize refinery runs and then sell the fuel to Europe.

Russia’s exports of diesel and gasoil to Turkey have climbed by 10.3 million mt on an annualized basis since the EU ban was implemented, according to Kpler data for the last three years. Flows to Brazil have increased by 8.1 million mt, with the balance mostly redirected to an array of countries in North Africa (5.6 million mt), the Middle East (4.8 million mt) and West Africa (3.9 million mt).

A source at the European Commission told OPIS that the original plan when the sanctions were designed was to reduce Putin’s oil revenues without “impacting global energy markets”, suggesting that they intended to slash Russia’s export prices rather than volumes, in particular for the global south. The sanctions were successful at harming Russia’s war effort, even if they haven’t met the expectations of some people, the source said.

The Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), a Finnish research organization, estimates that the sanctions have reduced Russia’s oil export revenues by 14%, or €34 billion ($36.9 billion) as of December 2023. “That impact, though, is far short of what could have been achieved,” CREA said.

Europe’s Diesel Consumption Plunges

And what about Europe? The continent, too, has found new trade partners. Compared with 2021 and 2022, the 27 EU countries and the UK increased diesel imports from the Middle East by 7.8 million mt on an annualized basis, by 5.8 million mt from the US, by 5.2 million mt from India and by 2.7 million mt from Turkey.

However, the bulk of the balance comes from lower overall diesel flows into Europe of around 10 million mt. With domestic refinery runs broadly flat in 2023 compared with 2022, according to data from the International Energy Agency (IEA), the supply deficit suggests that Europe has adjusted to the loss of Russian supply by reducing its own fuel consumption.

Indeed, the IEA estimates that diesel and gasoil demand in OECD Europe declined by around 200,000 b/d in 2023, which is roughly equivalent to 10 million mt. Collapsing diesel consumption in the continent has been mainly driven by an ongoing switch away from diesel cars. These are being replaced by new models of gasoline, gasoline-fuelled hybrids and, to a lesser extent, electric vehicles.

Automobile manufacturers recently reported that sales of new diesel cars in the EU slumped to just 1.4 million units last year. This compares with 6.6 million registrations in 2017, only six years earlier.

In addition, the European manufacturing sector remains in deep contraction, particularly in Germany, which is clearly weighing on consumption. Industrial activity is directly linked to diesel and petrochemicals demand.

Finally, heating use is also falling, as gasoil systems are replaced by gas boilers and electric heat pumps, and, crucially, the last two winters have been warmer than average.

In summary, Europe is now using less diesel and paying a premium to source it from further away. “Sending Russian crude to India, and then India sending products back to Europe – that adds a structural cost,” Calvin Froedge, the founder of maritime analytics platform Marhelm, told OPIS.

Moreover, James Noel-Beswick from Sparta Commodities said the EU ban on crude oil imports impacts diesel production at European refineries. This is because Russian crude has been replaced with other crude types that yield lower middle distillate output.

Shipping Costs Soar

Meanwhile, the reshuffle of traditional diesel trade routes into longer sea journeys is causing cargoes to travel further to their final destinations, which reduces vessel availability and, therefore, increases shipping costs – all of which eventually feed into the final fuel price.

“In our last update, we had LR (Long Range) 1 and LR2 tanker rates at just under $50,000/day; that’s an extremely strong rate. It used to be around $10,000/day prior to the invasion,” Calvin Froedge said. LR1 and LR2 are the types of vessels typically used to carry oil products from the Middle East and India into Europe, able to haul 60,000 mt and 90,000 mt, respectively.

Yet, on Jan. 26, just one week after OPIS spoke with Froedge, LR2 diesel tanker rates for the TC20 route from Jubail to Rotterdam had soared above $120,000/day. This was as companies chose to avoid the Red Sea due to Houthi attacks by diverting to the much longer Cape of Good Hope route, triggering a shortage of tankers and increasing shipping costs. As a result, European ULSD cracks widened to $33/bbl from $24/bbl in the span of three weeks.

“Europe has become very dependent on flows of Asian diesel and jet fuel via the Suez Canal due to the sanctions on Russia, and that is why those recent Suez issues are affecting European prices so much,” James Noel-Beswick told OPIS.

The disruption caused by the Houthis in the Red Sea is a good reminder of how dire the situation is for Europe. The continent is now significantly more exposed to supply shocks, as evidenced when French refineries were shut by strikes in the autumn of 2022 and spot diesel cracks soared above $80/bbl.

In short, European policymakers have been relatively successful at trimming Russia’s profits. But, in doing so, these officials have increased the price that EU citizens and companies pay for fuel. They have also left the continent more vulnerable to unexpected supply disruptions and have made it costlier for everyone to transport oil and refined fuels across the world.