Beyond Mid-May Motor Fuel Madness: Will Gasoline Supply Scrambles Persist?

The First Driver of the 2021 Motor Fuel Panic

In mid-April, a special report by Oil Price Information Service (OPIS) sounded an early warning signal for gasoline. Subscribers were told that for the first time in four years, the US gasoline distribution system might be hard-pressed to keep stations “wet.” In the jargon of downstream distribution, staying wet means never running out of fuel.

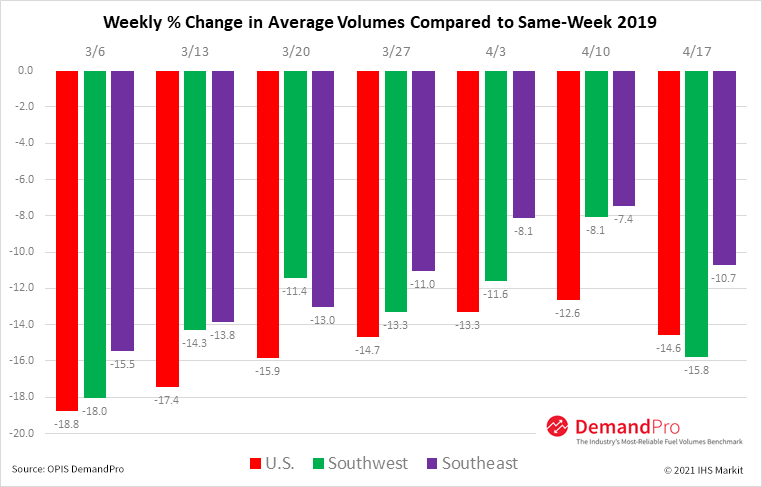

The prospect of dry stations came after spring break delivered occasional scattered outages of fuel in popular destinations in Arizona, Florida, and a few other states. It also came despite seemingly adequate supply as well as national demand that trailed 2019 levels by 10% or more.

OPIS’ original reporting detailed that thousands of drivers of tanker trucks left the work force in 2020 thanks to the COVID-inspired demand destruction as well as health issues in the pandemic. A typical pre-pandemic day might see 50,000 or more transport trucks on the road, each delivering about 8,000 gallons of gasoline and/or diesel to downstream fueling stations.

Thousands of drivers left that workforce, or retired, or moved to the less stressful realm of delivering goods ordered online. The closure of driver training schools, meanwhile, choked off the pipeline of new haulers. The loss wasn’t noticeable during the demand slump since transport truck shipments slipped to 25,000 to 30,000 deliveries per day.

“There has been a driver shortage for a while, now the problem has metastasized with the pandemic,” noted Ryan L. Streblow, executive vice president of the National Tank Truck Carriers industry group. “It’s going to be a problem for shippers, carriers and consumers across the board.”

Fallacies in Gasoline Demand Statistics

Beyond the dearth of drivers, there is another element of recent years that merits upfront attention. Gasoline demand has become extraordinarily “lumpy.” In 2019, the Energy Information Administration (EIA) showed weekly gasoline supplied as low as 8.565 million b/d and as high as 9.9 million b/d. The breadth between the low and high demand tides in 2020 was a never-before-seen 4.63 million b/d. Already in 2021, a gap of about 1.7 million b/d has separated the extremes and more variability may lie ahead thanks to a surge in pent-up vacations and “social driving.”

OPIS analysis published on May 21 underscores the issue and highlights the flaws in EIA data. The Weekly Petroleum Status report on May 19 implied a weekly demand surge of just 4.8% during the panic-laced week where millions of motorists topped off tanks in states impacted by the Colonial Pipeline shutdown. EIA does not measure actual sales but instead estimates inventory moving from primary or reported storage to secondary or tertiary destinations (stations, small bulk tanks, and cars). OPIS calculated a week-on-week volume surge in a similar period at 8.5%, a consumption spike about 77% above that implied by EIA. The persistence of outages in the week ending May 21 indicates that this week could see another large inventory drawdown and the highest gasoline demand reading since the Pandemic.

The week leading up to Memorial Day Weekend may also be problematic. Dramatic fluctuations in behavior can be created by the viral contagion that spreads via the “They Say…” prophesies in social and standard media that are never clearly sourced.

“They say we’re going to run out of gasoline” mantras provoked tank-topping behavior in states hundreds or even thousands of miles away from Colonial Pipeline infrastructure. Once that viral behavior spreads, common sense and facts have little influence. Witness the surge in gasoline consumption in southern counties of the Florida peninsula this month, a region which gets its fuel exclusively via barge or cargo ship.

The good news near-term is that Memorial Day Weekend is not so much a launch date for peak driving season as it is a dress-rehearsal for the 12-13 highest consumption weeks, which tend to occur between the summer solstice and Labor Day.

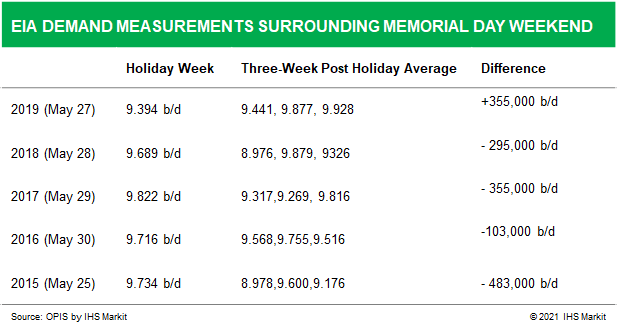

With the notable exception of 2019, the three weeks following Memorial Day Friday saw significant declines in gasoline demand. Six years ago, the drop was spectacular with demand sliding 756,000 b/d in the first June week. Smaller declines were measured from 2016-2018.

This year, the potential for an immediate June swoon in demand appears high. Panic behavior by motorists in the last half of May is no doubt “borrowing” from the ratable gasoline demand one might see in the first summer month.

Fallacies in Petroleum Supply Figures & an Imaginative Thought Experiment

The 6-day closure of Colonial Pipeline makes EIA days’ supply figures look more like a funhouse mirror than a true window on operational inventory.

Days’ supply are calculated by simply taking the amount of motor fuel in primary U.S. storage, and dividing that figure by recent demand, with a four-week average consumption level one of the favorite measuring tools. Using that methodology, days’ supply of gasoline has ranged between 26.2 days and 27.4 days since spring began, hardly hinting of any snags at the pump. The last year has seen some refinery closures that have lopped off about 1 million b/d of processing capability.

But some other statistics speaks to the “funhouse mirror” nature of days’ supply optics.

Back in 1981, for example, the U.S. population was measured at just under 230 million people. More recently, the population topped 331 million. Back in 1981, the US stored about 253 million barrels of finished and unfinished gasoline, or approximately 46.3 gallons per person. Gasoline storage last week was just over 234 million barrels. When compared to the population, there was about 29.7 gallons per person, a reduction of nearly 36 percent.

Just-in-time inventory practices have been the standard treatment for gasoline distribution for most of the last four decades. The practice made sense given the buildout of logistics, and the addition of about 4 million b/d of refining capacity from 1985 to 2020. Using the circulatory system as a metaphor, the U.S. had a much bigger heart and better arteries and veins.

But interruptions in supply (or demand as in 2020) can provoke extreme tides. By historical standards, the US gasoline distribution system is shallow, with a morphology similar to the famous Canadian Bay of Fundy, known for its tidal extremes.

And beyond those statistics, there are limits to what the distribution system can do when panic strikes the motoring public. The panic buying of mid-May 2021 was reminiscent of the hoarding during the Iranian Revolution of 1978-79 and the Arab Oil Embargo of 1973-74. Example: This month saw motorists follow transport trucks from terminals to gas stations and queued in lines absent since the era of bell-bottoms and classic rock.

Simply put, days’ supply becomes much less relevant when the teeming millions in the “crowd” become unmoored.

There may be more than 26 days’ supply of gasoline, but much of it is inside of refinery gates or was temporarily trapped during the Colonial downtime in pipelines and breakout storage tanks. (Note: those pictures of multiple steel tanks holding Colonial gasoline in Greensboro, NC are compelling, but none of the tanks can offload to transport trucks!)

And the distribution system was never set up to supply several days’ supply in a single 24-hour period.

Some quick arithmetic illustrates the problem.

A conservative estimate suggests about 280 million light duty vehicles in the U.S. that are fueled by gasoline. A ballpark number for tank ullage (the empty space left in a tank for fuel) might be 15 gallons. Hence, if a panic provoked everyone to fill up, the demand would be around 4.2 billion gallons, or 100 million barrels, translating into about 11 days’ supply based on the bulk inventory estimates. Put another way, panic buying or hoarding of gasoline can lead to more than ten times ordinary demand, creating thousands of station outages in its wake.

Conclusions and Predictions for Summer 2021

- The mid-May behavior of the crowd is a warning shot across the bow for orderly U.S. gasoline distribution. Pleas to “stay calm” simply stir up inappropriate behavior. The toilet paper shortage of 2020 is a valuable analog, and I suspect that days’ supply of Charmin or Scott were comfortable ahead of the pandemic. “Given the choice, the crowd will always choose Barabbas,” noted French philosopher Jean Cocteau, in an aphorism that suggests the crowd always makes the wrong choice.

- The crowd may get amped up when hurricane probability cones inevitably surface on the Weather Channel. This may be a zero-tolerance year for supply interruptions and the mere formation of a storm in the Gulf of Mexico will inspire hoarding. Perhaps isolation in the COVID era has made the crowd more restless.

- The safety net for bulk gasoline inventories is more tattered than it has been in years. COVID-19 inspired some key refinery closures that could haunt given regions of the country, particularly on the West Coast.

- The Colonial Pipeline shutdown was not a major pricing event for the futures’ markets or the spot markets where millions of barrels of gasoline (RBOB on CME) trade daily. Retail prices moved up unevenly and at times spectacularly in part because wholesale prices varied by as much as 30cts gal in specific markets.

- The driver shortage is real, and it will be top-of-mind for distributors and chain retailers through the driving season. Companies with in-house fleets have a huge advantage versus chains that commonly negotiate with carriers.

- Don’t be surprised to see government efforts to create strategic regional gasoline storage hubs. Gasoline is not a fine wine that can be stored forever, but politicians won’t let those details about specifications interfere with their efforts to leverage a good crisis for political gain.

- OPIS commonly has stressed that the move above $3 gallon in the national retail average was not a simple signpost on the way to $3.50 gal. National averages above $3.50 gal were common in the driving seasons of 2008, 2011,2012, 2013, and 2014. But those retail prices occurred against a monthly backdrop of prices for Brent crude well above $100 bbl and as high as $137.20 bbl. The bullish-beyond-consensus predictions this summer top out just above $80 bbl.

OPIS is able to provide comprehensive and in-depth historical analysis because it has a database of price history going back to 1980 for spot pricing data for gasoline, diesel and NGLs and 1995 for wholesale rack pricing for gasoline and diesel. You can easily access this same database for use with your analysis. TimeSeries is OPIS’ historical price database allowing on-demand access for users to pull historical price reports. It houses spot and wholesale rack prices for several energy commodities. Gasoline, diesel, NGLs, resid, feedstocks and futures history is available. Start a free 10-day trial and see for yourself.

–Steve Cronin, scronin@opisnet.com, contributed to this article.