Cap and Trade History For Fuel Markets

Leaders across the globe are racing to enact a greenhouse-gas reduction scheme that dates back to when the price of gasoline was less than 30cts/gal.

Cap and trade is rapidly becoming an environmental-policy phenom, amassing a fan club of lawmakers in North America, Europe and Asia.

But a look back at cap and trade history of shows it’s not a new idea. Scholars evaluated market-based climate-policy instruments as a method of meeting pollution reduction targets long before the 2015 global climate initiative named the Paris Agreement and the subsequent U.S. Climate Alliance in 2017 set off a wave of renewed interest.

More recently, in early February, the trend continued as officials from nine U.S. states formed the Carbon Costs Coalition – an alliance to cut greenhouse gas emissions by putting a price on excess carbon dioxide through cap-and-trade or carbon tax programs.

Last year was chock-full of similar proclamations by relatively small jurisdictions and even heavy hitters such as Mexico and China. Each is seeking ways to effectively reach stringent carbon emissions-reduction goals.

So why has this vintage system gained modern applause?

From an economic standpoint, cap and trade might seem a bit arduous. But in general, the concept is fairly practical – and even profitable.

A legislature puts a “cap,” or ceiling, on emissions, which is lowered each year in alignment with the program’s structure to reach pollution-reduction goals.

The “trade” part of the equation relates to the development of markets in which program participants buy and sell allowances (aka carbon credits) equal to 1 metric ton of CO2 equivalent.

Parties obligated to participate in the program have flexibility in a couple of ways. Entities can decide how to reduce emissions and may purchase carbon allowances at a quarterly auction or on the secondary market as needed. Entities surrender a portion of allowances each year as part of compliance.

Meantime, auction revenues are invested in greenhouse-gas-reduction programs such as building electric vehicle infrastructure. In addition, obligated entities that reduce emissions beyond expectations can sell unneeded credits to another obligated party for profit.

Market-based programs have evolved into multifaceted environmental solutions, but the basic principles of the system have remained mostly the same since inception.

Back to the Future

Cap and trade history traces back to the office of Thomas D. Crocker, an economics doctoral student at the University of Wyoming. It was the late 1960s, and Crocker was “teaching a heavy load of lower division undergraduate economic courses,” he wrote in a 2008 paper sent to OPIS in early February.

On a “gloomy Milwaukee day” he struggled to complete a dissertation, while a grant to study air pollution in central Florida “sustained [his] pride,” Crocker said in the paper titled “Trading Access to and Use of the Natural Environment: On the Origins of a Practical Idea.“ His mentor, professor Mason Gaffney visited him in his office and suggested that Crocker present on results from his Florida work at an upcoming conference in Washington, D.C.

“I didn’t yet have any,” Crocker wrote. “Instead, over about a month, I wrote ‘Crocker’ (1966), a paper now generally recognized as introducing the idea of tradeable permits for access to and use of the services of natural environmental assets.”

Speaking with OPIS by telephone from his nearly snowed-in home near Laramie, Wyoming, Crocker explained that cap and trade has increased in popularity because it’s the most cost-effective method of incentivizing an industry to reduce pollution.

Simply put, “the relative price is an incentive to induce behaviors,” he said.

But since its beginnings, cap and trade has fallen in and out of favor with U.S. lawmakers.

Through the years, market-based policies were innovations of presidential administrations.

For example, In the 1980s, an emissions-trading strategy was used to eliminate leaded gasoline from the market. And, in the ’90s, one was adopted to try to control acid rain caused by power plants.

California’s Plan

This decade, California lawmakers were the first to pick up the cap-and-trade torch in the United States.

The Golden State launched its emissions trading program in 2012 and is touted as an unofficial leader in climate change and cap and trade. Because its program is oftentimes seen as a benchmark, let’s look at California’s program for a deeper dive into how cap and trade works.

Program: At the end of July 2017, California Gov. Jerry Brown (D) signed Assembly Bill 398 into law, reauthorizing the state’s cap-and-trade program through 2030. Bill AB 32 – signed in 2006 – authorized the cap-and-trade program, which started in 2012.

The cap-and-trade program is just one part of the state’s climate playbook, the AB 32 Scoping Plan. This plan includes strategies to meet state emissions targets. California’s cap on emissions falls 3% each year between 2015 and 2020.

Goal: Reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 40% below 1990 levels by 2030 and 80% by 2050. In 2015, 440.4 million metric tons of carbon dioxide were emitted, according to the latest California Air Resources Board data. The two largest emitters by sector were industrial at 23% and transportation at 39%. Electricity generation was next at 11%.

Covered entities: California’s program covers hundreds of obligated entities, which produce more than 25,000 metric tons of CO2 equivalent annually. There are also “opt-in” entities, which act as obligated parties and “voluntary associated entities” such as compliance instrument brokers.

Allowances: The California Carbon Allowance (CCA) is the main instrument used to comply with the cap-and-trade program. Allowances are issued each year into a pool, which are auctioned quarterly.

Four percent of the allowances are held in a strategic reserve that are released if the CCA price gets higher than a preset level during auction. Like the emissions cap, the amount of available allowances decreases each year. Obligated entities are also able to keep private banks of credits. This is “to guard against shortages and price swings,” CARB said.

CCAs are classified by vintage or the year of issuance. The current vintage year is 2018, but previous and forward vintage years are also available. Most secondary market trade takes place on the ICE CCA futures contracts.

Another compliance tool is California Carbon Offset (CCO) credits, which can be used for up to 8% of a facility’s compliance obligation. Offsets are earned by emissions-reduction projects in the United States. Those project owners sell the relatively cheaper credits to obligated parties.

Compliance: Each year, covered entities turn in offsets and allowances for 30% of the previous year’s emissions. For example, in November 2017, CARB announced that all of the facilities covered by the program were 100% compliant, surrendering 30% of total obligations due for 2016. The remainder of the CO2 obligations are to be turned in this year, marking the end of a three-year compliance period from 2015 to 2017, CARB said.

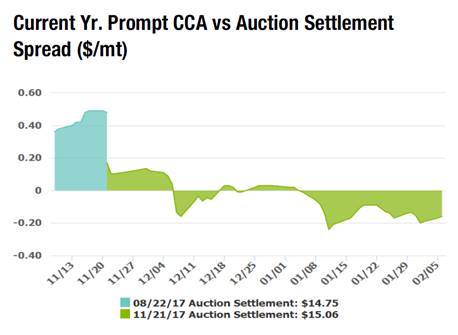

The chart above from the daily OPIS Carbon Market Report shows the differential between the daily current vintage CCA prompt price and the quarterly CCA auction settlement price.

Since the beginning of the year, OPIS’ Vintage 2018 CCA Prompt assessment, which represents the secondary market, has remained at a discount to the auction price. Some sources noted that secondary market prices were relatively weak on uncertainty surrounding Ontario’s Jan. 2018 entry into the California-Quebec cap-and-trade program. In addition, there were a lack of buyers in the CCA futures markets as obligated parties are stocked for compliance, they said.

Stay on top of the ever-changing carbon market with the OPIS Carbon Market Report, your single source for environmental credit costs.