The retail portion of the fuel chain is the most visible to the general public and likely the most complex to navigate.

Who Comes Up With Retail Gasoline Prices?

If you ask the average person who sets the price of gasoline at their local station, they might tell you that the station owner slaps the price tag on the pump – while shaking their head at how much their fuel bill eats into their monthly budget.

But that’s not really the case.

Buying fuel is confusing even for seasoned pros. We’re here to help.

The petroleum market features a slew of specialized fuel blends and no one-size-fits all requirement for what you can use — or where or when you can use it.

Whether you are new to the fuel industry or are already an expert, the words “spot,” “rack” and especially “basis” are terms that confuse even the most veteran buyer. There’s a good chance you or someone on your team may not be 100% sure what these words mean.

Why Is It Important to Understand These Fuel Pricing Basics?

Chances are you already have a fuel contract with a supplier in place. Maybe you are looking to set one up or modify one that already exists. Without a firm handle on what the difference is between futures, spot, rack and retail markets there’s a good possibility that you:

- Are unaware what the “cost basis” is in your fuel agreement

- Are not purchasing the right fuel for your area or paying too much for the fuel you buy

- Don’t understand what factors are making your fuel costs go up and down

Let’s clear up some confusion with a basic guide to pricing gasoline and diesel. Much of what you will learn here also applies to jet fuel, LPG and renewables.

Step One: Getting to Know the Futures Market

Before you can understand spot and rack prices, you need to understand the first piece in the downstream fuel puzzle: The New York Mercantile Exchange.

The industry commonly refers to this as the NYMEX or the Merc. Sometimes it is called “the futures market” or “the print.”

It’s a mostly electronic platform exchange, on which buyers and sellers can trade various fuel commodities — on paper — any time from a month from now to 18 months in the future. That’s why it’s called a “futures” market.

They call it a “paper” market because few, if any, physical barrels ever change hands. Trade volume is made up of contracts that transact among players.

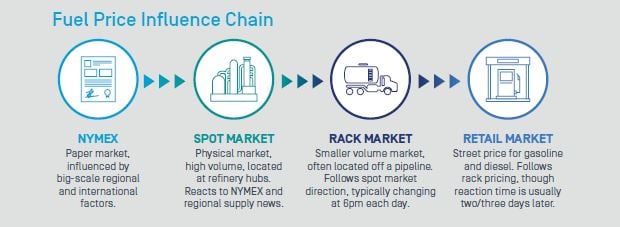

From here on out, to reduce any further confusion, we’ll refer to it as the NYMEX. The NYMEX is possibly the most influential factor in the upward/downward movement of wholesale rack markets. Oil futures affect spot markets, then rack markets, then ultimately retail markets.

The first energy contract was launched in 1978. Since then, the Merc’s launched contracts for:

- Crude oil (CL)

- Natural gas (NG)

- Ultra-low-sulfur diesel (HO)

- Reformulated blendstock for oxygenate blending, RBOB (RB, a blendstock that takes the place of a gasoline contract)

These abbreviations are what you’ll see on the trading screen, so add them to your alphabet soup full of acronyms to memorize.

Thanks for the History Lesson But What’s In This for Me?

One word: Transparency.

The NYMEX really took off as a major factor in the U.S. petroleum market back in the 1980s because it was the only place refiners, suppliers, traders, jobbers, retailers and procurement end-users had full access to see the value of a commodity at any given time.

The transparency was generally not for real barrels of crude oil that you could turn into gasoline. Remember, this is mostly a paper market – physical delivery only occurs for 2% to 3% of all contracts on the current NYMEX. But, at that time, unlike today, there was no downstream price discovery.

So, the futures market became a place where fuel buyers or sellers could go to find a cost basis for fuel supply agreements. This is why, when we talk about the NYMEX, we start to introduce the concept of “basis.” More on that later…

Since the 80s, price transparency has extended to the spot market (the refinery level) and rack market (the wholesale level). We’ll dive deeper into those markets in the sections that follow. But, that clear level of transparency has always remained on the NYMEX.

In addition, the exchange is regulated by the CFTC (Commodity Futures Trading Commission), adding a level of accountability to every 1,000-barrel, or 42,000-gallon, contract traded.

The paper market is used to hedge physical fuel purchases – kind of like insurance for prices rising or falling, to protect the companies holding contracts from losses related to their physical energy business. But, for our purposes right now, the critical point is that it is the primary building block of

downstream gasoline and diesel pricing.

There are two other key elements about the futures market:

- First, the trades are anonymous.

- Second, and most importantly, the exchange guarantees counterparty performance. No chance of an Enron-like implosion here.

However, the Block Is Rarely Stable

However, the Block Is Rarely Stable

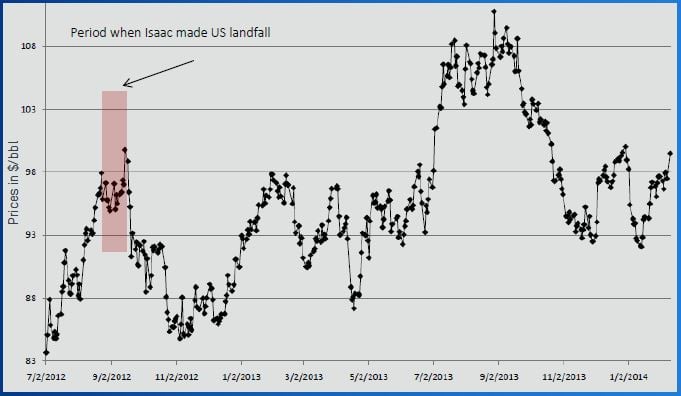

Military conflicts, hurricanes, domestic refinery problems, fluctuations in domestic output abound. Often, the first trace of any breaking news is seen on the futures screen, because oil prices spike and dive.

Take a look at this chart to see how Hurricane Isaac sent futures flying and how the market volatility continued.

The NYMEX tends to react to big-ticket items, like:

- Currency market moves

- Geopolitical “saber rattling”

- OPEC decisions

- Supply reports, like the weekly U.S. inventory and production figures

- Refinery explosions

- Weather events

Sometimes the market “prices in” so-called fundamental factors. For example, if the U.S. government is expected to show crude stock supplies falling by a large amount, the market might slowly crawl higher in advance of the weekly inventory report as opposed to rallying sharply when expectations prove true. On the other hand, a quickly developing weather event can lead to immediate price swings.

And the market also responds to seasonal trends. For example, the RBOB market tends to peak ahead of summer driving season. The ULSD contract (a proxy for heating oil) will often spike on the first chilly fall day.

Some terminology you will hear when people talk about the market:

- Bullish – the market is rising

- Bearish – the market is weakening

- Oversold – the market is rising

- Overbought – the market is weakening

But, What Does This Mean in a Market That Trades ACTUAL Barrels?

The NYMEX is the first column in your price equation. If RBOB futures go higher, it will send gasoline prices up right through the fuel chain — unless the next link in the chain does something to counteract it.

Understand the fuel chain from start to finish with this helpful e-Book from OPIS.