CBAM 101: The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism Explained

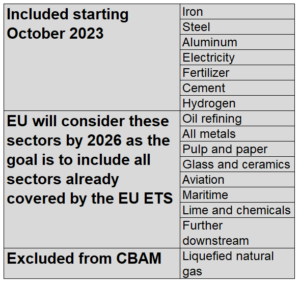

Starting Oct. 1, 2023, importers of downstream products including iron, steel, aluminum, electricity, fertilizers, cement and hydrogen into the European Union will need to report the carbon intensity level of these products to the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) Authority on a quarterly basis.

Importers won’t have to pay any carbon levies just yet but are expected to do so by 2026 when the CBAM enters into full effect. While the CBAM will cover these sectors first, it’s highly likely that this tariff will increasingly include more downstream products and indirect emissions and, by 2030, cover all the sectors under the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS).

What is the CBAM?

To understand the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), we need to understand the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), the carbon market that will determine the price of CBAM certificates, in other words how much importers will need to pay to cover the cost of emissions embedded within their imports.

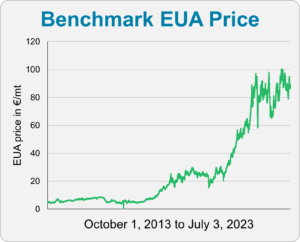

Since 2005, the EU has required industry within its borders to pay a market-based carbon cost under the EU ETS. In theory, the EU ETS aims to incentivize manufacturers to invest in decarbonizing by applying the principle of “polluter pays.” This means the more carbon dioxide an operator emits during manufacturing, the more money it should pay. With a limited number of EU carbon allowances (EUAs), which are expected to disappear by 2039, the price of pollution is expected to increase over the coming years. Exporters and importers in the EU will now have to keep the price of EUAs in mind: EUAs reached an all-time high in February, trading as high as €100.70 ($106.54)/mt and, more recently, traded at €85.27/mt on Sept. 25, 2023.

Since 2005, the EU has required industry within its borders to pay a market-based carbon cost under the EU ETS. In theory, the EU ETS aims to incentivize manufacturers to invest in decarbonizing by applying the principle of “polluter pays.” This means the more carbon dioxide an operator emits during manufacturing, the more money it should pay. With a limited number of EU carbon allowances (EUAs), which are expected to disappear by 2039, the price of pollution is expected to increase over the coming years. Exporters and importers in the EU will now have to keep the price of EUAs in mind: EUAs reached an all-time high in February, trading as high as €100.70 ($106.54)/mt and, more recently, traded at €85.27/mt on Sept. 25, 2023.

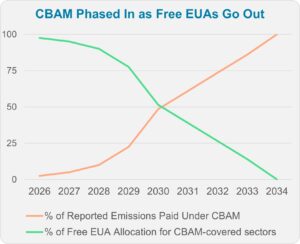

Within the EU, the bloc provides hard-to-decarbonize sectors such as steel and cement manufacturers with free EU carbon allowances. However, with the introduction of the CBAM, this free allocation will be phased out gradually. EUAs will come to an end entirely by 2034 as the CBAM is simultaneously rolled out.

Essentially, free EUA allocation will be out and CBAM certificates will be in.

The CBAM is part of the EU’s Fit-for-55 reform to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 55% based on 1990 levels by 2030. The CBAM was provisionally agreed to by EU bodies in December 2022 and finally adopted by the EU Council in April 2023.

With the EU having the most expensive carbon allowance in the world, entities sending their products to the EU will face the high carbon costs that EU industry is currently required to pay. According to the EU, the CBAM “would mirror the EU ETS effects for non-EU producers” and “encourage other countries to establish carbon pricing policies.”

What is Reported Under CBAM?

EU importers will have to monitor and report the carbon emissions embedded in the products in question to the newly-created CBAM Transitional Registry on a quarterly basis starting Oct. 1, and the first report is due by Jan. 31, 2024. Importers won’t have to pay the carbon levy until Jan. 1, 2026.

Those reporting data will need to provide: the total quantity of each type of product based in metric tons; the installation where the product was made; the total number of embedded emissions in tons of carbon dioxide for each ton of the product; country of origin and carbon price paid abroad.

Those reporting data will need to provide: the total quantity of each type of product based in metric tons; the installation where the product was made; the total number of embedded emissions in tons of carbon dioxide for each ton of the product; country of origin and carbon price paid abroad.

When the CBAM enters into full effect starting Jan. 1, 2026, the EU will require importers to file annual declarations by May 31 each year. The declarations will detail the amount of carbon emissions embedded in imported products during the last calendar year and how many CBAM certificates will be required to cover those emissions.

For countries that already include a carbon cost — for example, China also has its own ETS albeit at a substantially lower cost than that of the EU — European importers will have to prove that a carbon price has been paid in a third country. As a result, the importer can deduct that cost from the CBAM certificate.

Parties that do not report their CBAM declarations will face penalties of between €10 to €50 per metric ton of unreported emissions.

Importers are those who will need to purchase the CBAM certificates, which will be calculated on the average weekly auction price of the EU ETS. If there are no auctions in a given week, the average of the previous week stands. CBAM certificates cannot be traded and will have limited validity.

What Will the Next Few Years Look Like for CBAM?

The transitional phase, from Oct. 1, 2023, to Dec. 31, 2025, will correspond to sectors with the highest risk of carbon leakage and with the highest carbon intensity in their products: iron and steel, cement, fertilizers, aluminum, hydrogen and electricity.

The EU has said that the CBAM would eventually cover more sectors and that indirect emissions would also be included.

The full CBAM will come into force on Jan. 1, 2026.

“With this enlarged scope, CBAM will eventually — when fully phased in — capture more than 50% of the emissions in ETS-covered sectors,” the EU said. “The objective of this transition period is to serve as a pilot and learning period for all stakeholders (importers, producers and authorities) and to collect useful information on embedded emissions to refine the methodology for the definitive period.”

By 2030, the EU will likely extend the CBAM to cover all of the sectors already included within the EU ETS such as oil refining, upstream, all metals, pulp and paper, glass and ceramics, imports related to the aviation and maritime shipping sectors, and lime and chemicals.

What Does This Mean for Energy Trade?

As CBAM takes shape over the few next months, more and more countries with existing carbon schemes are considering implementing their own CBAMs. Earlier this year, the Australian and British governments voiced their support of a carbon tariff; countries like the US, Canada and Japan are considering doing the same.

Other countries like India and China, both of whom are among the world’s largest steel producers, have shown their opposition to the EU’s carbon levy, calling it a protectionist measure and bringing up complaints to the World Trade Organization. According to consultancy firm Wood Mackenzie, the carbon costs on steel alone could amount to a 56% increase for India and a 49% increase for China by 2034.

As exporters to the EU face climbing carbon costs, many will likely divert their carbon-intensive products to countries without carbon levies while sending less carbon-intensive products to the EU.

According to Wood Mackenzie, prices on commodities and products are likely to rise in the EU and low-carbon producers will have the chance to seize higher margins within the EU market. The consultancy firm’s research shows that the CBAM could provide more than $9 billion in revenues from the covered sectors by 2030.