The US Shale Revolution: A Look Back at a Decade

A decade ago, something dramatic — and largely unanticipated — began to emerge in the US natural gas industry. At the time, we dubbed it the “Shale Gale.”

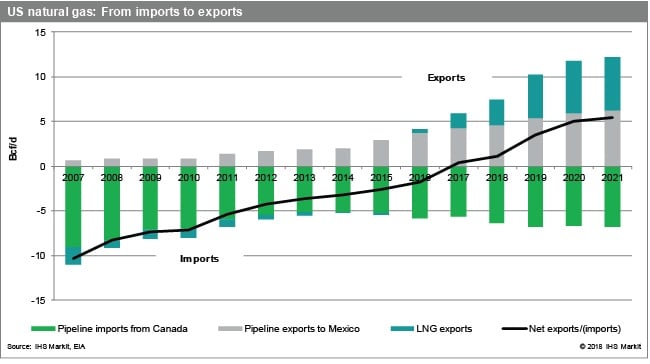

What has transpired since then is both a dramatic surge in output and a wholesale turnaround, a veritable revolution in the industry. It has transformed the US from an importer of natural gas into an increasingly important exporter (see graph below). The impacts extend beyond the natural gas industry itself. The Shale Gale has also transformed the overall US energy industry, shifted company strategies, and dramatically changed global energy markets.

- The blog is excerpted from a report published by OPIS parent company IHS Markit in June 2018 titled, ‘US Natural Gas: After ten years, shale provides major strategic asset for the US.’ Daniel Yergin, IHS Markit Vice Chairman, and Samuel Andrus, IHS Markit Executive Director, are co-authors of the report. Get the full report here.

Part of the explanation for shale’s development lies in regulatory change and the freeing of markets.

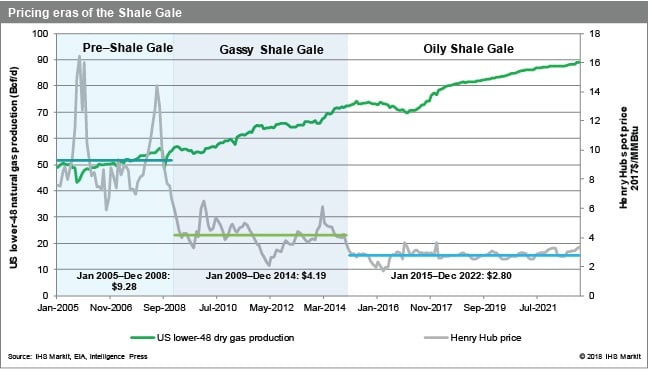

The decontrol of natural gas prices was initiated under the then President Jimmy Carter and completed by former President George H. W. Bush. Market pricing, in place of administratively determined prices, stimulated drilling for new gas. The result was new supplies. These supplies, together with pipeline restructuring, opened an era of moderate prices — to the surprise of many who had opposed the lifting of price controls. Indeed, supplies became so ample that they created a decade-long oversupply that became known as the “gas bubble.”

But, around the beginning of the twenty-first century, the market changed. The drill bit was producing declining amounts of gas, supplies were becoming tight, and prices were going up. There was a widely held assumption that the domestic supply base was being exhausted and that the US would have to become a major importer of liquefied natural gas (LNG) — perhaps the world’s largest.

Yet, at the same time, although largely unobserved, advances in and yoking together of two technologies — horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (fracking) — were beginning to access heretofore commercially unavailable gas that was trapped in shale rock and tight formations. A growing band of independent producers seized upon the new technology to develop new gas resources. The relatively high natural gas prices of this period, reflecting the overall tight supplies, provided the incentive for experimentation and risk-taking by these independents. However, this new development went largely unnoticed or was regarded as something that was suited only for the business model of independents and the modern-day version of “wildcatters.”

The Supply Surge

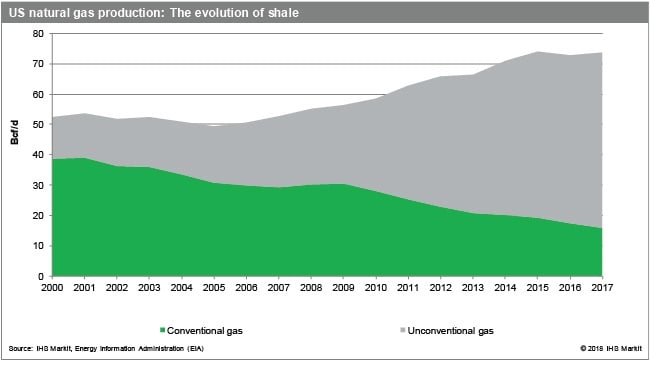

As the combined technologies were applied more widely, US gas production surged to such an extent that this turnaround in US gas supply was dubbed the “Shale Gale.”

The turnaround has been striking. For the eight-year period of 2000–07, total US natural gas production grew less than 1%. However, over the subsequent 10-year period of 2007–17, output grew 41%. And the pace of growth is accelerating. For 2018, we expect natural gas production to be up 7 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d) relative to 2017. Altogether, we anticipate that US production could grow by about another 60% over the next 20 years.

With broad recognition of resource availability, supplies grew, and prices declined. What had been expected to become an increasingly scarce and expensive resource was now abundant and inexpensive. Between 2007 and 2017, US natural gas production grew from 51.7 Bcf/d to 72.6 Bcf/d. Gas’s share of total US energy consumption rose from 22% in 2006 to 29% in 2017.

The Big Flip: From Imports to Exports

As already noted, the informed assumption prior to 2007 was that the US was going to be a major importer of LNG, perhaps the world’s largest. On that basis, construction had already begun on several facilities for importing LNG, regasifying it, and distributing it to US consumers.

But then, as the Shale Gale’s intensity grew, it became obvious that higher-cost imported LNG would have no market in the US. Not only were LNG imports not required, but US pipeline imports of natural gas from Canada declined from a peak of about 16% of domestic supply in 2005 to about 7% currently.

Moreover, and contrary to what had seemed settled wisdom, it became clear that the growing volumes of gas were exceeding domestic demand and that the US could sell natural gas into international markets while still easily meeting its own growing demand. By the beginning of 2018, the US was exporting 4.4 Bcf/d (worth about $5 billion per year) via new pipelines to Mexico — about 6% of domestic production but close to half of Mexican natural gas needs.

The dramatic expansion in US natural gas production has meant a 180-degree turn, enabling the US to become an LNG exporter, rather than an LNG importer. Plants that were originally envisioned as LNG receiving terminals have been reconfigured as LNG liquefaction export terminals, at the cost of tens of billions of dollars. New greenfield projects have also been initiated.

The first new major US LNG export terminal dispatched its first cargo in February 2016. Since then, US LNG exports have ramped up to 3 Bcf/d, and LNG has been delivered to a total of 26 countries by vessel: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Malta, China, the Dominican Republic, Egypt, India, Italy, Japan, Jordan, Kuwait, Lithuania, Mexico, Portugal, South Korea, Spain, the Netherlands, Pakistan, Poland, Taiwan, Thailand, the United Arab Emirates, Britain, Turkey, and Colombia.

We expect that, over the next five years, the current nameplate liquefaction capacity of 3.1 Bcf/d of LNG exports will grow by another 6.9 Bcf/d.

The Impact on The Power Industry

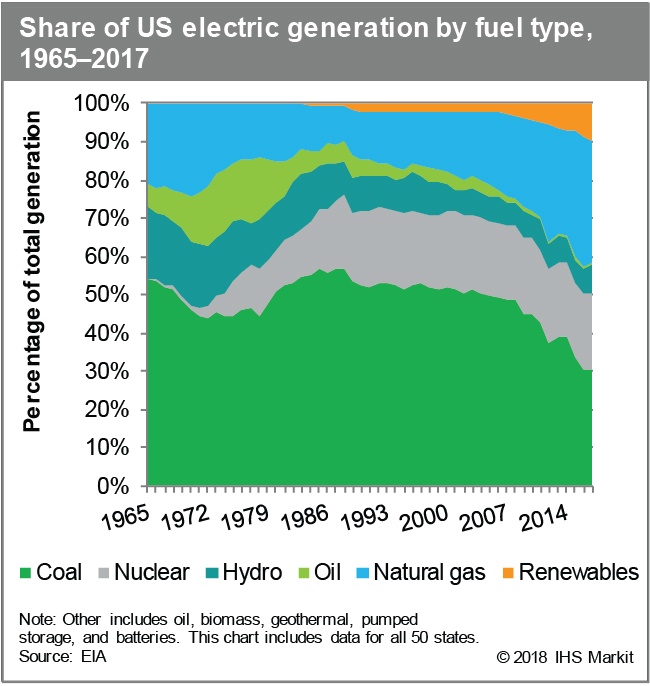

The shale gas revolution has transformed power generation economics, resulting in a rebalancing in fuel choice for electric generation.

In 2007, coal provided 49% of US generation and natural gas provided 22%, and more than 10 GW of coal generation was under construction. In 2016, natural gas overtook coal for the first time and supplied 34% of total electric generation while coal supplied 31%. In 2017, there was a slight reverse shift, with 31% of generation provided by coal and 30% by natural gas. Gas has become a backbone of electric generation in the US.

Conclusion: The Impacts Are Wide-Ranging

Overall, the unconventional revolution has dramatically altered the outlook for US natural gas over the past decade. Once considered to be in imminent danger of depletion, the US natural gas resource base is now widely agreed to be sufficient to last into the twenty-second century at current rates of consumption. Costs have also fallen, and natural gas prices are expected to increase very slowly over the next 20 years — remaining lower than prices for many other fuels.

The new outlook for natural gas cost and availability has created new possibilities for making progress toward national goals of energy efficiency, cost efficiency, environmental protection, and energy security. It is also contributing jobs and revenues to the economy at the national, state, and local levels. In short, the Shale Gale has put a powerful new wind at America’s back.

This blog was excerpted from a report published by IHS Markit in June 2018 titled, ‘US Natural Gas: After ten years, shale provides major strategic asset for the US.’ Daniel Yergin, IHS Markit Vice Chairman, and Samuel Andrus, IHS Markit Executive Director, are co-authors of the report.