While you’re flipping burgers in your backyard on the grill, take a few minutes to think about your propane tank – other than wondering if you need take it in for a refill.

The propane itself in that cylinder making those perfect grill marks possible is a pretty interesting gas liquid that has a worldwide presence and millions of barrels and gallons originate from Mont Belvieu, TX, a town you may have never heard of.

What Is Propane?

There is a class of hydrocarbons called natural gas liquids (NGL) that occur as gases at atmospheric pressure and as liquids under higher pressures. Of all the natural gas liquids traded, from ethane to natural gasoline, propane is the most liquid.

Propane, a clean burning fuel, can be used for residential purposes in heating homes and cooking; in fact, many household appliances that run on heating oil, wood, natural gas and electricity can be replaced with propane. Propane can also be used for industrial and commercial purposes in industrial furnaces and kilns, fuel in fork lifts, bus fleets and autogas. It is also part of the petrochemical feedstock chain to make other chemicals and plastics.

How Does Propane Fit into the Global Energy Market?

Much of the new millennium witnessed an enormous increase in the domestic production of shale gas, with production encompassing the Ohio River Valley to Texas, the northern part of America, along the Gulf Coast and certain interior states as well. That had a huge impact on the global LPG industry.

Fractionation of shale plays and the expansion of the oil and gas industry has enabled U.S. to move from an importer to a net exporter of natural gas liquids, specifically propane. Back in 2016, the U.S net exported 24.9 million mt of propane/butane. And by 2023, the U.S. net exported 59.7 million mt of propane/butane with imports amounting to just 235,000 mt.

While propane may be unique in many ways, its journey from a bonded carbon molecule to a cylinder is subject to a supply chain as any other fuel and has its own spot market.

On an average trading day, propane constitutes the highest volume among all NGL traded in the NGL spot markets. It then is bought and sold at the wholesale and retail level and ultimately makes its way to the end user or customer.

The highest-profile hub of the propane spot markets in North America is Mont Belvieu.

Mont Belvieu? Where Is That?

Mont Belvieu in Texas has naturally occurring salt dome formations that serve as storage facilities for propane and has extensive access to pipelines, gas processing facilities and waterborne terminals.

This small town has emerged as the nucleus for propane processing, witnessing an enormous expansion in infrastructure provided by the industry players operating in the region. A superhighway of pipelines connects to storage, major refineries, fractionators, PDH (propane dehydrogenation) units and import and export assets. With its strategic location along the U.S. Gulf Coast, Mont Belvieu has emerged as a prominent export facility for trading propane.

Why Do Mont Belvieu Propane Prices Matter?

For the propane industry players – producers, suppliers, retailers, wholesalers – it is critical to keep an eye on the Mont Belvieu spot market. OPIS provides the official spot benchmark for propane prices in Mont Belvieu.

Interconnectivity a Key Component of Mont Belvieu’s Importance

Because of the immense network of pipeline and waterborne infrastructure that carries propane and other NGLs out of Mont Belvieu’s processing nexus, the trade movements in this small Texas town have influence well beyond its borders.

- The OPIS North American Propane Ticker is one way to see how prices in Mont Belvieu relate to those in the Conway, Kansas hub, all the way north to Canadian spot markets.

- Meanwhile, the OPIS Global LPG Ticker shows Mont Belvieu pricing in relation to markets in Europe and Asia, giving market participants a quick reference point to decide whether its economical to ship internationally.

What’s Next for the Propane Markets? Two Major Game Changers

About two decades ago, online trading of propane and other NGLs was a relatively new concept. These days, online platforms along with voice brokers have really grabbed hold of the market and have been game changers for liquidity.

Of course, we also see shale plays continuing to have a major role in shaping the market for gas liquids and continuing to help solidify the U.S. role as a net exporter – with Mont Belvieu featuring even more prominently.

The numbers really don’t lie. Back in 2014 the U.S. contributed to 19 percent of the global LPG supply. The U.S. contributed to 43.7% of global propane/butane supply in 2023, according to data from shipping analytics firm Vortexa.

So, expect big things from this unassuming clean burning fuel that powers your backyard grill.

Live spot propane price updates increase your flexibility to react to changes in the market. The North American Propane Ticker updates spot prices from market open to close, providing up-to-the-minute price indications for Mont Belvieu TET, Non-TET, Other Non-TET, Conway In-Well, Hattiesburg In-Line, Alberta and Sarnia, Edmonton and Ontario.

Fun fact of the day: refiners, generally speaking, don’t make gasoline.

Drivers may think that crude oil goes into a refinery and gasoline comes out.

That’s only partially correct. Think of making gasoline as making a cake. There’s flour, eggs, milk, and oil in a cake recipe. Gasoline is similar in that it has multiple components that make up the gasoline recipe. At the end of that recipe you have two types of almost finished gasoline called Conventional Blendstock for Oxygenate Blending and Reformulated Blendstock for Oxygenate Blending.

To these blendstocks other liquids are added to make the substances that fuel our carpools, take us to grocery stores and get our families to their summer vacations. And, mostly, that final mixology does not happen at the refinery level.

The Mixers: CBOB and RBOB

To reiterate, most of the gasoline produced by refineries is actually unfinished gasoline or gasoline blendstock.

Blendstocks are blended with other liquids, such as ethanol, to make finished gasoline.

Most of the finished gasoline in the US contains 10% ethanol.

The blendstocks are a mix of components such as butane, reformate and FCC gasoline, which can be combined in different ways to reach needed specifications.

Conventional Blendstock for Oxygenate Blending (CBOB) is a blendstock that’s combined with ethanol to get E10 gasoline.

Reformulated Blendstock for Oxygenate Blending (RBOB) becomes reformulated gasoline (or RFG) after blending with ethanol.

What’s the Difference Between RBOB and CBOB?

Reformulated gasoline is required in certain areas to reduce smog per Clean Air Act amendments. RFG is required in cities with high smog levels and is optional elsewhere. RFG is currently used in 17 states and the District of Columbia. About 25 percent of gasoline sold in the US is reformulated.

Many of the RFG areas are in the mid-Atlantic and Northeast. So, OPIS spot market editors see a lot more Reformulated Blendstock for Oxygenate Blending (RBOB) trading in the New York Harbor region.

In the Gulf Coast spot market, Conventional Blendstock for Oxygenate Blending (CBOB) tends to be the most liquid product because there are fewer areas requiring RFG in that region.

Where Does Ethanol Enter the Picture?

Ethanol is like the icing on that cake made from gasoline. (Eww. Please don’t eat it.)

The use of ethanol is largely linked to the advent of the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) program, which Congress enacted to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, expand the US renewable fuels sector, and diminish US reliance on imports.

Ethanol isn’t blended into gasoline blendstock at the refineries, largely because ethanol can’t be transported through pipelines. It would damage them. Strong stuff!

Instead, ethanol is most often blended in at the rack, closer to its ultimate destination. That’s why you’ll often see ethanol listed along with gasoline and diesel in rack prices.

Ethanol serves to boost octane levels in gasoline, which can be helpful. But it also raises Reid Vapor Pressure (RVP), which can be tricky.

RVP measures the volatility in gasoline and is subject to seasonal mandates. So, blending ethanol can be complicated during summer months, when people are looking for lower-RVP gasoline.

Sometimes, detergents or other additives are blended into gasoline before it hits retail stations—those additives are a way that fuel brands differentiate themselves with customers.

Happy baking!

Demand for voluntary blue carbon credits from companies seeking to fulfill net zero pledges has surged in recent years, but geopolitical risks, limited verification capacity and high startup costs will likely prevent blue carbon credit supply from scaling up for years to come.

Companies want blue carbon credits — which are generated by coastal carbon sequestration projects — for their high quality and ability to diversify carbon storage portfolios.

But blue carbon projects account for just a handful of the 2,158 projects registered by Verra, a leading carbon credits registrar and verifier.

From April 21, 2022: ‘Huge Momentum’ is Underway for Blue Carbon

High demand for the credits and relatively expensive project costs have pushed the offsets to a substantial premium over forest-based credit alternatives in the voluntary carbon market.

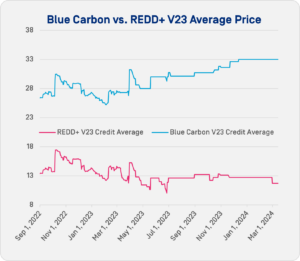

OPIS calculated the Blue Carbon V23 Credits Average at $33.01/mt on March 13. On the same day, the REDD+ V23 Credits Average was calculated at $11.71/mt.

“It’s what everyone wants, but no one can get,” Arthur Wace, sustainability consultant with London-based carbon risk management and procurement firm Redshaw Advisors, said. “We have clients that have made net zero commitments for 2030 or even 2025. They want to invest in projects now. But the risks are too high.”

“It’s what everyone wants, but no one can get,” Arthur Wace, sustainability consultant with London-based carbon risk management and procurement firm Redshaw Advisors, said. “We have clients that have made net zero commitments for 2030 or even 2025. They want to invest in projects now. But the risks are too high.”

Sources said there are a few reasons for that, including that the blue carbon verification and credit issuance system is still in its early stages.

Project methodologies continue to develop, and it remains difficult and costly in many parts of the world to accurately measure the carbon stored in blue environments.

Further, it requires significant startup capital to begin to restore a coastal environment and it takes years to realize profits from credit sales. And many countries with blue carbon projects have yet to decide how to govern them. “The market is not in a position to scale,” Wace said. “But we’re getting there.”

Carbon Accumulation Rates Vary

As methodologies develop and researchers learn more about blue carbon environments, their climate diversity and carbon storage capacities are becoming clearer. Coastal mangrove forests, salt marshes and seagrass beds typically store carbon at a higher rate than forests and for longer periods.

Scientists estimate wetland environments store carbon at 10 to 20 times the rate of land forests, but others caution that comparisons are tough to make because of wide variations in both ecosystems. And while coastal wetland environments around the world are under threat globally, there’s no risk of them burning during periods of drought.

From April 20, 2022: Blue Carbon Pioneer Says Mangrove Tree Is the ‘Best Climate Machine’

A research team led by University of North Carolina Professor Antonio Rodriguez studied carbon deposits in salt marshes along North Carolina’s coast. In a study published in July in Nature, the group detailed the variations that occur depending on the age and growth of the ecosystem.

“If you look at carbon burial at different time scales, you get vastly different values,” Rodriguez said.

When salt marshes degrade, they begin to release the carbon they have stored.

But when restoration begins, as Rodriguez and his team found, carbon accumulation rates are high. Rates plateau as the ecosystem matures, but most of the carbon sucked from the atmosphere remains.

“That’s really important for offsetting because if you restore a salt marsh, then you’re going to benefit from that increased burial right away,” he said.

What’s more, as sea levels continue to rise, researchers expect the area viable for salt marshes will expand.

‘Can we even do this?’

Liz Guinessey is Verra’s food and blue carbon innovation manager and wetlands expert. Before that, she investigated GHG emissions and carbon storage in Georgia’s coastal wetlands for her master’s thesis.

“Back then, it was this question of, ‘Can we even do this? Can we get the quantification down pat enough to be able to potentially bring this carbon that gets stored to market?'” Guinessey said.

Despite the challenges, she said Verra has managed to develop ways to do so with confidence. “I think we’ve been able to figure out ways to deal with that uncertainty, deal with those fluctuations, and still be able to very clearly estimate at a conservative level what’s actually stored,” Guinessey said.

Still, blue carbon credit verification remains a developing practice. Verra released its first blue carbon methodology in 2020 and has since added three more. The organization is now in the process of consolidating the three into a single document.

Competing registry Gold Standard has not finalized blue carbon methodologies, although it said it’s developing a mangroves methodology with FORLIANCE.

Sources also said it can be challenging to find researchers with the expertise needed to verify a blue carbon project’s impact. And it’s a dirty job.

“Most are muddy, mucky environments,” Guinessey said. “You get literally absorbed by mud a lot of the time. These are not great conditions for field work. But I think that we’re getting to a point where it’s not becoming as challenging, especially with new technologies like remote sensing.”

Geopolitical Risk

As blue carbon methodologies develop and experts learn to understand and measure the environmental conditions, governments have grown wary of voluntary projects.

In one case, the blue carbon project known as Tahiry Honko was launched in 2014 by UK-based Blue Ventures and 10 small communities in Madagascar.

But in 2018, the Malagasy government argued the communities had signed a bad deal and placed a moratorium on the sale of carbon credits. None from the project have been sold, according to Mongabay, an online conservation news outlet. A number of voluntary offset projects that predate the moratorium remain in limbo.

Actions by other governments could also affect the projects.

India’s Power Minister Raj Kumar Singh in August announced a ban on the exports of carbon credits, though the government has offered no further information.

Some sources believe Singh was referring to carbon credits that would apply to India’s new compliance market, rather than those that would be sold on the voluntary market.

In recent months, Papua New Guinea, Honduras and Indonesia also have announced moratoriums on the sale of some credits. And many other countries have stepped in to regulate the voluntary market in some way.

“So many of these coastal systems are considered public goods under different jurisdictions,” Guinessey said. “So, getting either the government to sign on to a carbon project or figuring out some sort of concession to allow for a group to move in and actually develop a project can be a barrier.”

Where Are Blue Carbon Credits Headed?

Along with geopolitical risks and limited global blue carbon credit capacity, project finance is also a problem. Restoring blue environments is costly and it can often take several years before developers are able to start selling credits.

A number of companies are working to reduce the risks of carbon offset projects in general. Verra is developing credits that can be sold to generate startup capital to projects just getting off the ground. Insurance providers have also begun to underwrite projects against the potential invalidation of credits issued.

Still, the barriers to entry, particularly for communities in developing countries, remain high, sources said.

Analysts, however, expect buying interest in blue carbon credits will continue to rise.

“There is a general undersupply, and these projects are perceived to be of very high quality,” Anop Pandey, manager of market analysis for ClearBlue Markets, said. “We believe that any new supply will certainly get bought up quickly.

Also, as offset usage by corporations continues to receive more scrutiny, there will be more pressure for corporations to show the offsets they are using are of a high quality with large emission reduction and removal benefits.”

Stronger demand for the credits and price premiums are helping development efforts.

“In 2019-2020, you could buy a carbon credit from a REDD+ project for $6, $7,” Wace said. “Now, as prices have come up, we can begin to bring on higher impact projects.”

At the same time, the buyers for blue carbon offsets are mostly large tech companies with significant cash flows.

“Will other corporate industries be willing to pay for these projects?” Pandey asked. “In other sectors with companies that have smaller budgets for offset purchases, but still have high emissions, maybe not. As such, the demand and supply of these projects will need to find a balance.”

Blue carbon projects face other risks, including the environments’ ability to survive and continue to sequester carbon for decades.

During six-month period in 2016 and 2017, for example, between 40 and 50 million mangrove trees in Australia’s Gulf of Carpentaria died. The culprit was an exceptionally harsh El Nino climate that dropped coastal water levels by 40 centimeters for roughly six months.

Still, with cooperation between government and private industry, experts expect blue carbon credits will eventually provide a crucial, high-quality means of carbon sequestration at scale. But it remains impossible to say exactly when that will come to pass.

As the weather warms up with summer on the horizon, US gasoline prices will likely follow the season’s temperatures and start the cyclical rise as well.

Why does gasoline typically cost more in warmer weather months?

One of the biggest reasons for the price change is RVP, or Reid Vapor Pressure. It’s a measure of gasoline volatility. For those technically inclined: the number is the absolute vapor pressure of a liquid (in this case gasoline) at 100°F (37.8°C) as determined by the Reid method. In layman’s terms, it’s the ability of gasoline to vaporize so it can be used in your car’s engine – which changes with the outside air temperature.

That seasonality is a big part of the reason gasoline gets more expensive as temperatures increase. The lower the RVP, or the lower the volatility, the more expensive it is to make on-road gasoline. The summer months, when ambient temperatures are higher and gasoline evaporates quicker, require a lower pressure. In colder temperatures, gasoline with a higher RVP is preferred for winter driving.

Apart from car performance needs, the US Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, sets standards for summer RVP levels to reduce emissions from evaporating gasoline, which can contribute to smog.

Part of understanding RVP is understanding how gasoline is made.

Gasoline isn’t just refined and ready to be put into your car’s gas tank. It must be blended with multiple components to make something that is able to be used on the road – like baking a cake with many different ingredients. And all those ingredients – or blending components in the gasoline-making world – must add up to a final product that you can put in your car, meeting all the specifications that make sure it’s up to snuff. And all those components affect the final product in different ways.

For example, take butane – a popular component for blending gasoline in wintertime. Butane is an inexpensive way to increase the octane (which means the resistance to knocking or uncontrolled ignition within a car’s engine) in your blend of gasoline. However, butane also increases the RVP level, so it is mainly used in the winter months, when RVP specifications are high.

So how does this affect the cost of gasoline, from the retail station to the wholesale racks to the big bulk gasoline markets?

Those less expensive (and sometimes more plentiful) blending components like butane, which can be used during cooler weather, help to keep the price of gasoline down at the pump. But as the weather gets warmer, some of those components aren’t going to be able to be used and more expensive options will have to be utilized.

Typically, consumers start to see prices head higher in the spring and early summer as blends make their way to the pump gradually as the weather warms – with timing that can vary by region. The change at your local gas station can depend on several factors besides the change in RVP, like local margins, competitive factors, etc.

But upstream, those changes start much sooner than they do in the retail sector. In the rack markets, where marketers go to load up their fuel trucks, usually the specification shift happens in spring as markets across the country start to supply the lower RVPs (LRVP). In 2024, OPIS Rack Reports will start to reflect LRVP starting as early as April 1 and continue through September 15 for most areas. The EPA mandates that terminals are fully switched over to summer-spec fuels by May 1, but refiners often start the process earlier.

Every city in the US is required to switch to a 9.0-lb. RVP gasoline in the summertime, with several areas across the country requiring even lower (and more expensive) RVPs. For example, the Sparks/Reno rack in Nevada will only show 7.8-lb. RVP products and the Detroit, Michigan, rack will only show 7.0-lb. RVP material.

Even further upstream from the rack markets, in spot markets, where large volumes of incremental material change hands (i.e. trades of 5,000 – 25,000 bbl or more), the RVP shift takes place even sooner.

As of March 1, 2024, California CARBOB gasoline has already moved to a 5.99-lb. RVP gasoline for the summer. East of the Rockies, Group 3 is showing an 8.5-lb. RVP specification, while Gulf Coast markets are showing a transitional, 11.5-lb. RVP grade product to help downstream customers blend tanks to lower RVPs but will see summer-spec gasoline appear in early March. Chicago and New York Harbor markets are still showing a winter-grade, 13.5-lb. RVP, summer grades of gasoline making their appearance later in March.

RVP transitions play a large role in the changing price of gasoline, as regulations must be met to have viable gasoline product for use at the pump. But there are a myriad of other factors that can mitigate or exacerbate any of those changes – including geopolitical influences, price movement of futures contracts, weather events, regional supply disruptions and refinery issues, to name just a few.

OPIS provides several tools to help keep abreast of the changing prices and regulations, such as the OPIS Spot Ticker, spot market reports, rack reports and retail data, as well as alerts for breaking news that can influence the price of gasoline.

With the integrity of carbon offsetting under fire, buyers are looking to lock down the forward delivery of high-quality credits from trusted climate projects, but there’s just one problem: some offset project developers don’t want to play ball.

From accusations that climate projects have disadvantaged local communities to claims of fraudulent carbon credit issuances, market proponents have weathered a hail of criticism in recent months. In response, some corporate buyers have ramped up purchasing due diligence and pushed for contracts that guarantee a fixed volume delivery over time.

This last point has given some sellers pause, such as Kennemer Eco Solutions Co-Founder and Technical Climate Lead Florian Reimer.

“For us, as a new market entry developer with only two projects, we would never sign such a liability,” Reimer said. “I think many smaller developers would feel uncomfortable with that.”

Hunting High-Quality Credits

During the last eighteen months, the voluntary carbon market has been characterized by trade illiquidity and a slump in prices after growth surged through the first half of 2022.

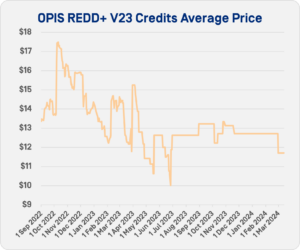

The OPIS Voluntary REDD+ Credits Average current-year price declined to below $12.50/mt in March 2024 from a peak of above $16/mt in October 2022.

The OPIS Voluntary REDD+ Credits Average current-year price declined to below $12.50/mt in March 2024 from a peak of above $16/mt in October 2022.

According to analysts, corporate purchasers are growing more careful.

Project developers have mostly kept up with bolstered demand for high-quality credits, but that may be changing. Credit retirements across the five largest registries outstripped issuances in 2024 until the last week of February. As of March 10, 48.2 million credits had been issued and 42.2 million had been retired.

Current market dynamics also reflect scientific debate over emissions reduction baselines and the volume of carbon that projects sequester, as exemplified by reporting in January from U.K. news outlet The Guardian.

Conditions have been exacerbated by the fact that the voluntary carbon markets are still structurally and operationally underdeveloped, sources said.

The Rocky Road to Project Revenue

It can take several years of work and significant investments before a climate project yields any income.

Climate projects are often built in a shifting, dynamic landscape, prone to upheaval from natural and human forces, and verifiers can only estimate potential emissions reductions. Actual credit issuances might significantly exceed or miss those expectations.

If a project is sufficiently capitalized, this last point is irrelevant because the developer can afford to wait for credits to be issued before it sells them.

But if a developer needs to fund operations before credits are issued, it may sign contracts that promise credit delivery on a forward basis.

The Role of Forward Delivery

Industry stakeholders generally agree that forward delivery contracts can play a crucial role in developing the market. But once the details of forward emissions reduction purchase agreements come into focus, buyers and sellers sometimes find themselves at odds.

One key sticking point involves the volumes of credits delivered. Some ERPAs (known as proportional forward ERPAs) require the project developer to deliver a percentage of the credits they ultimately issue. Others prescribe a fixed volume for future delivery (and are known as fixed forward ERPAs).

For a fixed forward contract, a developer must make up the difference if their project doesn’t produce enough credits to fulfill the order.

“New carbon projects launched by smaller developers are high-risk ventures,” Reimer said. “The buyer or investor is usually the financially stronger party.

“This is an early-stage capital investment associated with high returns but also high risks,” Reimer added. “I think smaller developers argue that those parties need to carry the risk of delayed issuances, and traditionally that has been the majority of cases. We find no problem in financing our projects via forward contracts without a replacement credit liability.”

Fixed forward contracts, however, are becoming more commonplace, and developers’ ability to avoid such circumstances may be shifting.

In February 2023, the International Emissions Trading Association released framework ERPAs intended to serve as a blueprint. The IETA forward ERPA included language that secures fixed forward delivery.

If a carbon offset credit shortfall “beyond the reasonable control of the Seller” occurs “the Seller shall instead be obligated to Transfer Comparable VCCs in an equal number to the shortfall and otherwise in accordance with this Agreement as soon as reasonably possible,” according to the document.

This Primary ERPA (along with a related Contingent Secondary ERPA) “is intended to provide a minimum benchmark for transacting emissions reduction and removal credits by including basic provisions relating to the transaction of such credits,” according to an IETA news release.

Are Strong Risk Protections Counterproductive?

The company Respira manages a portfolio of high-quality voluntary carbon offset credits. According to CEO Ana Haurie and Director of Business Development Will Close-Brooks, it prefers to sign proportional, not fixed, forward ERPAs.

“When you’re trying to contract on a forward basis, you need to build risk mitigation into your arrangements,” Haurie said. “We just need more certainty. I hope that high-quality project developers won’t be put off one way or the other.”

Close-Brooks said, “We want the project [with which we transact] to continue to be viable and to be successful. So, I would say we’re very interested in mutually sharing risk and trying to be pragmatic.”

Mike Korchinsky, whose conservation organization Wildlife Works is primarily funded through REDD+ credit sales, sees another wrinkle in this dialogue.

“We believe in market mechanisms,” Korchinsky said. “We have seen the evolution of the market from its origin. [Fixed forward ERPAs] are going to work well for high-volume buyers in the global North. Oftentimes, that’s at odds with the people who actually bear the cost, the true cost of change.”

In Korchinsky’s view, the local and indigenous communities that often must change their way of life to support a project are too-often ignored in transactions. If too many deals occur that don’t adequately serve their needs, they could grow reluctant to collaborate.

“Imagine a community that has begun work on a carbon project,” Korchinsky said. “It hasn’t received any funding for the work it has done. Then the project doesn’t deliver for whatever reason. They can be held accountable to the buyer for the market value of replacement credits. It’s not malicious; it’s short-sighted. If the buy side tries to be too self-serving, it can be counterproductive.”

Voluntary carbon credits forward delivery contracts are unique for another reason. Unlike other sectors, the contracts can’t be easily used to secure funding from a third party. That reality has frustrated ALLCOT CEO and Founder Alexis Leroy, whose business develops both renewable power and carbon offset projects.

“If I were building renewable power, I could get a power purchase agreement, walk into the bank the next day, and they would finance 75%, 80% or maybe even more than 100% of the project,” Leroy said. “But with an ERPA, no bank in the world would provide us with capital.”

Risk Tools, Insurance Enter the Picture

Still, the IETA ERPAs only represent a starting point in negotiations. Contracts signed by sellers and buyers tend to be highly specific depending on project specifications. Forward carbon offset insurer Kita CEO Natalia Dorfman has witnessed this firsthand.

“Any time you negotiate a contract where the two parties don’t necessarily have a view of what everyone else in the market is doing, you create the potential for imbalances on either side,” Dorfman said. “I’ve seen ERPAs that are wholly unfair to the project developer. I’ve seen somewhere the buyers are taking on significant amounts of risk. And I’ve seen others that are less than a page in total. One of the key challenges within the market is that it lacks the basic underpinnings it needs to scale.”

Contract reform, furthermore, isn’t the only tool stakeholders have at their disposal. Insurance providers, including Kita, Parhelion, Howden Group Holdings, Oka and others, have begun to underwrite aspects of VCM projects and transactions.

“Even with the best ERPA, all it can do is pass risk up or down the chain, ultimately to the buyer or the seller of the offset,” said Parhelion CEO Julian Richardson. “The problem with this is that contract counterparties might not be willing or able to accept the risk. There is no point forcing your counterparty to accept the risk if their balance sheet is limited or they are not creditworthy. By bringing highly rated insurance paper to the table, we are giving counterparties a creditworthy third party to transfer the risk to.”

A number of carbon credit ratings agencies, such as Calyx Global, Sylvera and BeZero have also launched to provide third party credit quality information.

“In terms of securing future ‘quality’ supply, this is a super interesting topic,” said BeZero CEO and Co-Founder Tommy Ricketts. “The surge in pre-issuance market activity, notably for engineered and nature-based removals, has come with rising calls from our clients for pre-issuance risk tools. Not surprisingly that’s something we are investing in heavily. I think that will be a big trend for 2023.”

Passenger traffic totals at Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) in July 2023 reached 7.308 million, representing a 15.17% increase compared to the same period in 2022, according to the latest data released by Los Angeles World Airports, the owner-operator of LAX and Van Nuys Airport.

On September 14, 2023, front month WTI futures surpassed $90/bbl for the first time since November 2022.

Six European Union-based plants operated by five cement industry giants — Holcim Group, CEMEX, Buzzi Unicem, Votorantim Cimentos and Cementos Portland Valderrivas — were issued a surplus of €88.2 million ($95.2 million) in free European Union emissions allowances (EUAs) from 2019 to 2022 despite the installations being idle or emitting tiny amounts of carbon in a calendar year, an OPIS review of EU data shows.

The loss of access to Russian crude and unusually high summer temperatures have curbed output of oil products from European refineries, the International Energy Agency (IEA) has warned.

Prices and cracks for diesel and other oil products surged in late July and early August, reflecting tight supply and low stocks at a time when demand picks up due to the summer travel season.